This is a crosspost from VanessaSaurus, dinosaurs, programming, and parsnips. See the original post here.

I recently contributed to a project, and a maintainer pinged me apologizing that it didn’t show up in the Twitter preview for the changeset. The problem was that it showed him as the committer because it was cherry picked.

Now reader, I had already been graciously thanked and felt appreciated for the contribution. But he brought up a good point - sometimes with large git histories, or if the final product is squashed and merged or cherry picked, we can lose sight of our contributors. This I think is a bad thing, because as a maintainer I want to champion my contributors. We should have an automated way to quickly say:

Show me the contribution summary for this repository between the last release and this one!

So this was (one of) my fun projects to tackle this weekend!

CiteLang

To sidetrack for a moment, one of my personal projects, a library called CiteLang is aiming to make an effort to redefine credit for software. Now, that’s another post in and of itself, but I’ll briefly summarize for those interested. If you aren’t interested, jump down to the contrib section. CiteLang takes the approach that trying to generate some digital object identifier (DOI) is too much extra work to reasonably do. I mean seriously, do we really need to follow a dated academic practice that champions a unit of worth as the publication when we know that process is broken? We need to move away from this traditional “be valued like an academic” model. I am troubled that I don’t see anyone really going for this. All I see is our community trying to write more papers about citation? That is very ironic. So although I can’t change it overnight, I can at least try and introduce new ideas, and put my money where my mouth is by implementing them.

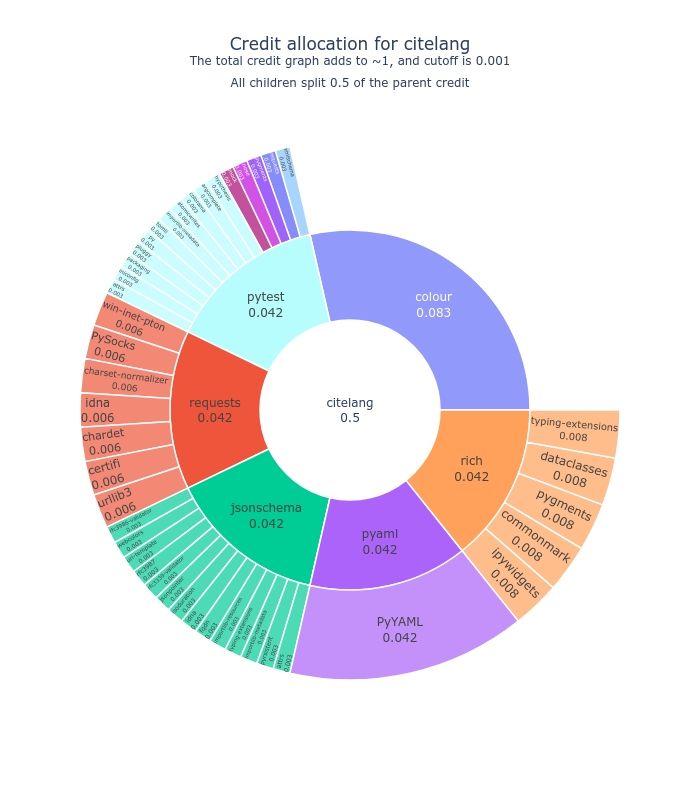

This is why I created CiteLang. CiteLang takes the approach that the unit of “publication” for a piece of software is when it’s added to a package manager, meaning that anyone else can use it within that manager’s domain, and “publishing” or getting credit means doing what you would or even should be doing for software anyway. So what CiteLang basically does is provide a client and Python functions for taking some package from a manager, and generating credit summaries in markdown, or even badges for a repository. Here is the badge for CiteLang itself. We give some credit split (50%) to the library itself, and the other half goes to the dependencies, and this pattern continues to their dependencies up to some minimum credit threshold. It makes a nice sunburst:

I haven’t written it up formally yet because I’m still working on it quite a bit, but I suspect I will at some point!

CiteLang Contrib

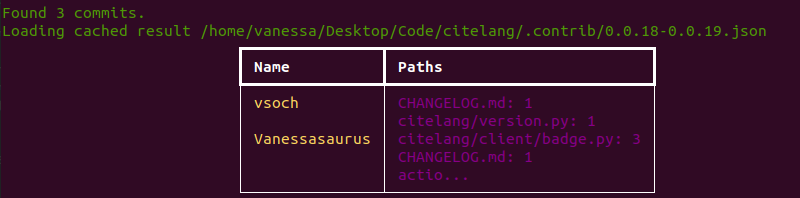

A “contrib” command for CiteLang made sense because it’s a different level of credit attribution. Instead of looking at the package manager metadata, we instead want to look at the git history. However, we want to look into the deepest level of contribution - the actual contributions for commits on a line to line bases! This means that we can use git blame. What a git blame can show us, for some point and time (commit) and file, is the last person that contributed each line. This means that if you look at a file over time (commits) you’ll see duplication if the line has not changed, and we need to be careful of this if we are counting contributions. So first, let’s run citelang on itself! Here we can see detailed contributions, by author, between two tagged releases:

$ citelang contrib --start 0.0.18 --end 0.0.19 --detail

What you see above is a (truncated) listing of files, authors, and lines changed. It’s truncated for display in the table. If you wanted to save this data to an output file, you can get the complete story:

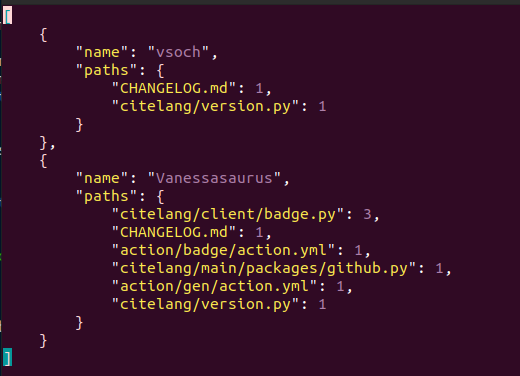

$ citelang contrib --start 0.0.18 --end 0.0.19 --detail --outfile citelang-18-to-19.json

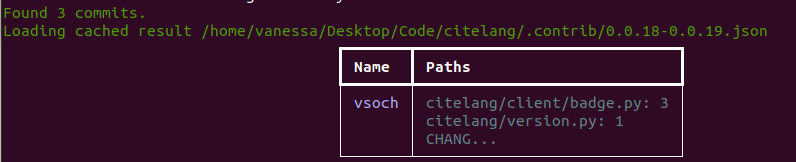

That also shows that sometimes I commit as vsoch, and sometimes Vanessasaurus. :_) If I make an alias lookup file, I can tell CiteLang that “Vanessasaurus” is in fact “vsoch”:

$ citelang contrib --start 0.0.18 --end 0.0.19 --detail --filters citelang-authors.yaml

And this author duplication is fixed!

Contrib for Singularity

It’s more interesting for a larger project like Singularity! Here is the same thing, but for an old version of Singularity, between 2.3 and 2.3.1. Note that I’m sitting in the root of the repository when I run this:

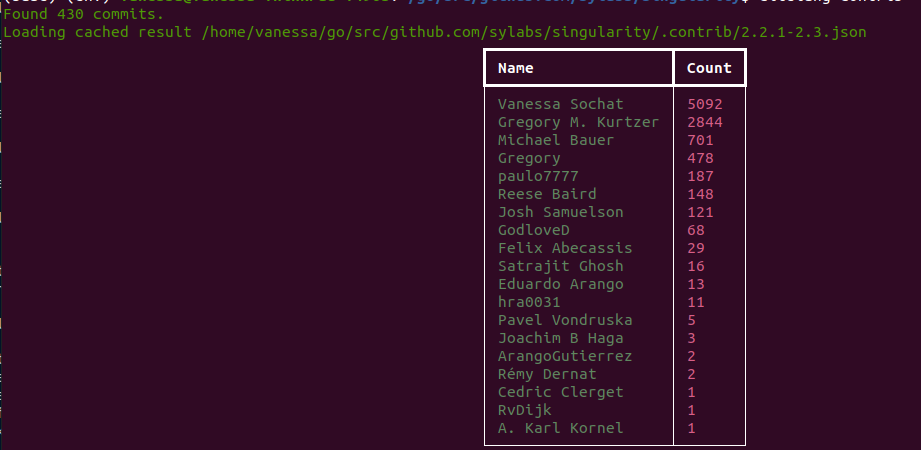

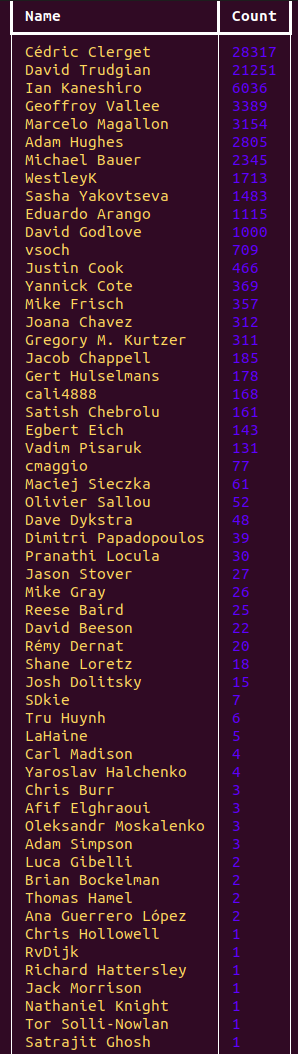

$ citelang contrib --start 2.2.1 --end 2.3

or with detail:

$ citelang contrib --start 2.2.1 --end 2.3 --detail

Again, the detailed view truncates fairly arbitrarily, so it’s just a shapshot. We could change this at some point but the table could get VERY large. Here is an example of a range that had cherry picking where (if you look superficially at the release) you miss the contributors:

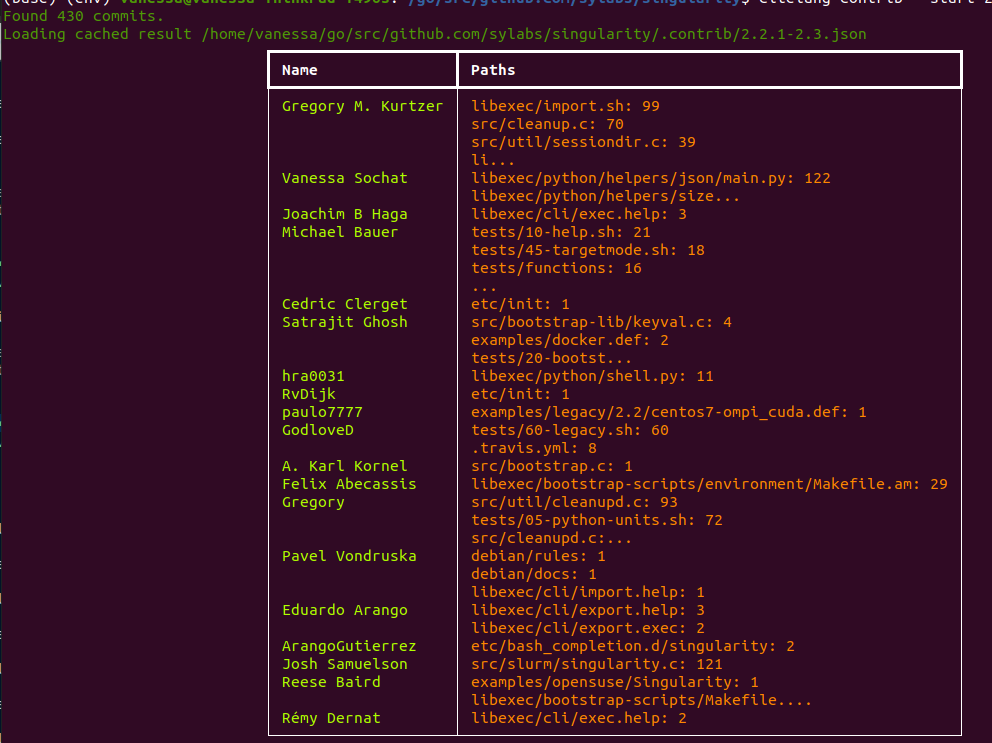

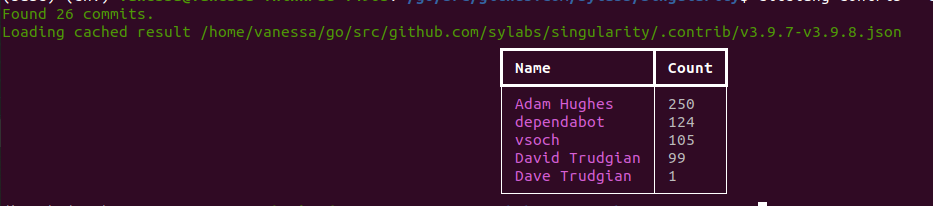

$ citelang contrib --start v3.9.7 --end v3.9.8

Include All Blames

We also might say “Hey, show me that range of commits but include credit for all time, meaning blames (commits) that are still present in the time we are interested in, but perhaps were created before it.

$ citelang contrib --start v3.9.7 --end v3.9.8 --all-time --filters authors.yaml

This barely fit on my screen, but it did! And actually, I again used that --filters flag

so we can associate a specific name with one author alias. It was when I was looking at Singularity

that I realized that I needed this filtering functionality, because I wanted to remove bots,

match aliases, and ignore some random commit by “root” (although I think I know who that was!)

Here is what that filters file looks like:

authors:

Vanessa Sochat: vsoch

Cedric Clerget: Cédric Clerget

cclerget: Cédric Clerget

ArangoGutierrez: Eduardo Arango

Marcelo E. Magallon: Marcelo Magallon

Ian: Ian Kaneshiro

sashayakovtseva: Sasha Yakovtseva

jscook2345: Justin Cook

GodloveD: David Godlove

Dave Trudgian: David Trudgian

Gregory: Gregory M. Kurtzer

ignore_bots: true

ignore_users:

- root

Update citelang also now has support for ignore_basename and ignore_files to not parse

specific files, such as go.mod and go.sum that are automatically derived and should not count toward credit!

With this change we also tweaked the parsing to not count empty lines, since no code is actually written there!

Note that you could also use this alias functionality to assign people to groups (companies,

organizations, labs, etc.) as a different way to summarize. And special shoutout to the main group

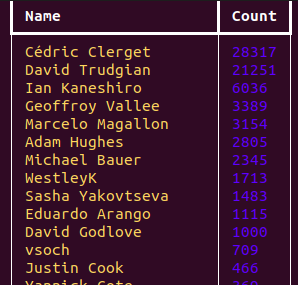

of guys at the top (yes it is all men, I can say guys) before my GitHub username that have been the

powerhouse behind Singularity.

I see many names from Sylabs, and even before. It’s surprising that I have that many lines of blame still somewhere given that I largely stopped working on the project at the end of 2017. Cedric and Dave Trudgian are superheros!

Summarize by Path

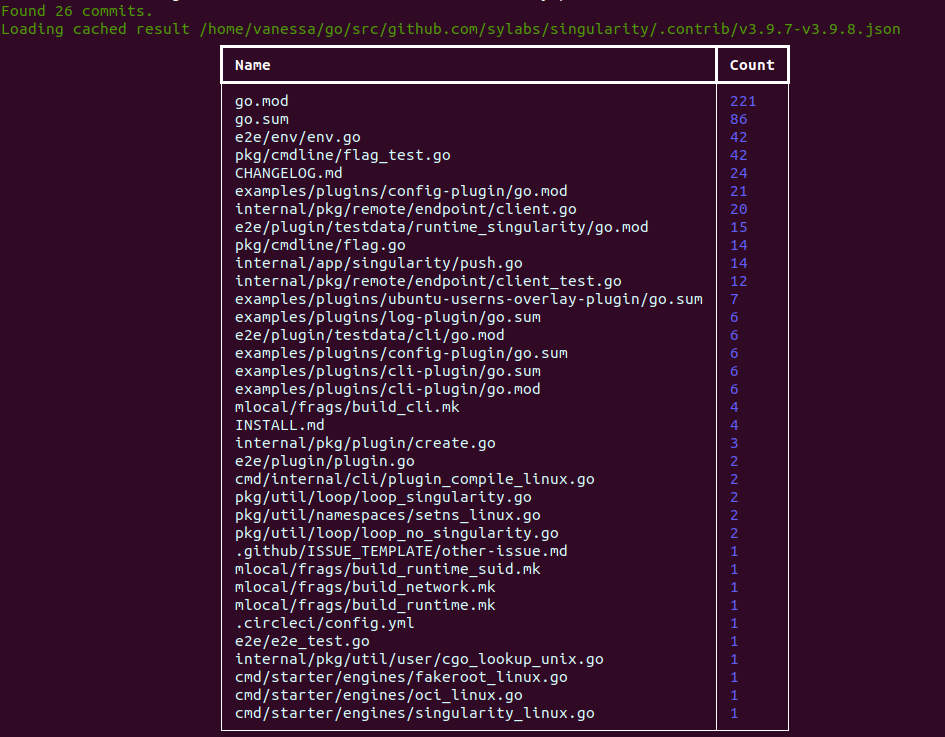

We can also decide we want to summarize by the file instead of the author, for example if you want to see the most changes files for the range based on lines changed.

$ citelang contrib --start v3.9.7 --end v3.9.8 --by path

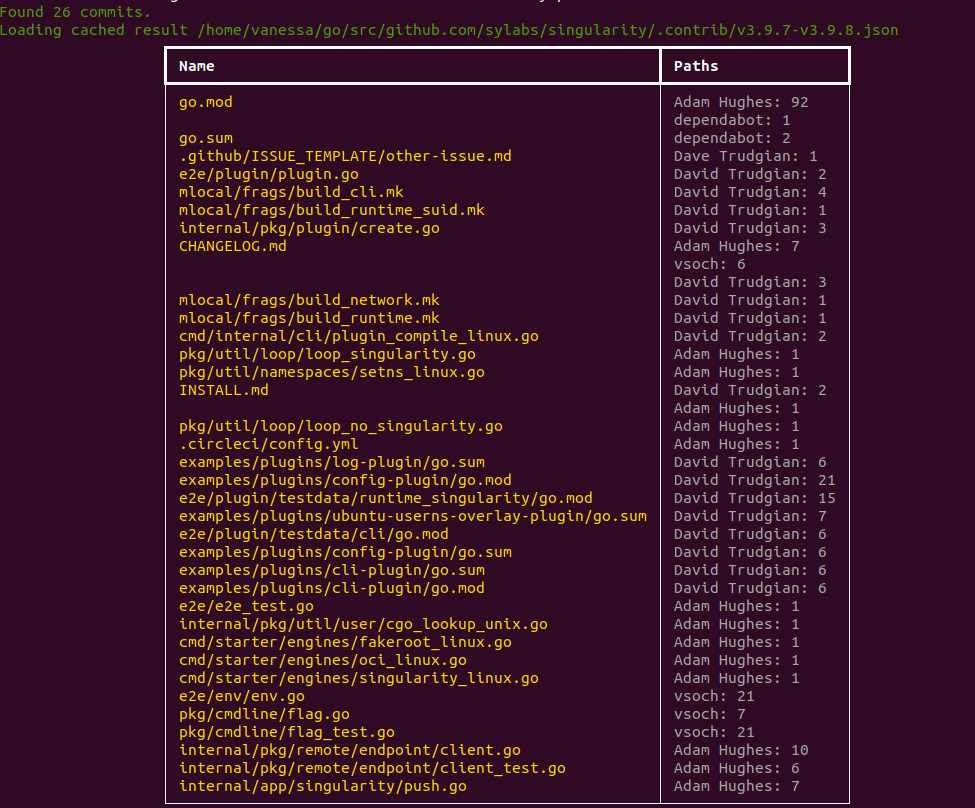

…and add details (in this case the author and not the path, and again truncated for display).

$ citelang contrib --start v3.9.7 --end v3.9.8 --by path --detail

And that’s the basic functionality! I’ve created both this interactive “quickly see” and export data, along with a GitHub action that you can use to generate the data. I’m planning (in a future evening or weekend) to make a more structured GitHub action paired with an interface to automatically display contributions. Mind you I just threw this together today so likely I’ll work more on it.

How does it work?

I decided early on I wanted to use git blame - the reason being that we want to get the original, fine-grained contributions. We also want to take account for the amount of work that a person puts into a contribution. It’s not to say that more code is always better, but if the practice is always to squash and merge, a single commit isn’t the right granularity to measure because it could be one or 1000 lines.

This means that deriving credit is a bit slower because we have to run git blame across files and commits, but with multiprocessing I was able to get ranges of commits to run in a reasonable amount of time. What you’d likely want to do for a huge repository that you want to study over time is save the cache of blame results, and then incrementally grow it with each release. I will likely provide this when I provide some kind of action or UI in the future.

git blame

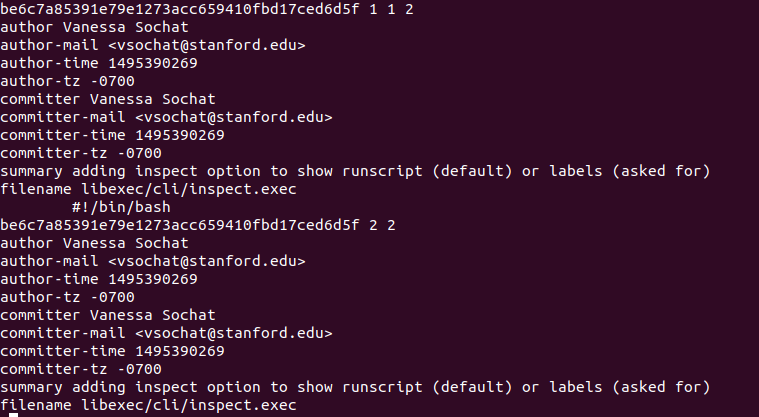

But I digress! So first let’s talk about git blame. When we run git blame on a file we get the last commit and timestamp that every line was modified. Here is an example, again with Singularity:

$ git blame -w -M -C --line-porcelain e214d4ebf0a1274b1c63b095fd55ae61c7e92947 -- libexec/cli/inspect.exec

There you see two lines under the same commit that were changed, and we count each one. Note that the above commit can be derived from a tag name as follows (and this is what the library does):

$ git rev-list -n 1 2.3.1

From the above entry we save:

- The author name

- The path

- The text

- The commit

- The timestamp

The timestamp is especially important because by default we want to honor the request to see

a particular range, and don’t include git blame commits that happened before or after it.

You can disable this with the --all-time flag. The primary use case, as you might imagine,

is that you are maintainer releasing a new version of your software and you want to give a manual

or programmatic shout-out to the contributors between the last release and this new one.

So the way that contrib works is to:

- Take a start and end tag or commit to parse

- Find the range of commits relevant to that range

- For each commit, find all relevant changed files

- Run git blame for the commit and file, and save a cached result (the fields above)

- Each multiprocessing worker returns the complete blame result

- We combine results across workers

- We then filter down to timestamps within the range (if not all time)

- We organized based on author or path, and with or without detail

- The result is printed or saved to the filesystem as json

For the fourth step, we run jobs with multiprocessing, and we store the result in the .contrib

cache, which is organized equivalently to the repository. This means that future workers can

immediately find and load the file instead of running git blame (and parsing that result) again.

For example, here is Singularity after a run, and we can see there are files from both the

golang history and the previous bash/C++ and python history:

$ ls .contrib/cache/

alpinelinux bin configure.ac debian examples INSTALL.md ...

AUTHORS CHANGELOG.md CONTRIBUTING.md docs go.mod internal ...

AUTHORS.md cmd COPYING e2e go.sum libexec ...

autogen.sh CODE_OF_CONDUCT.md COPYRIGHT.md etc INSTALL LICENSE ...

This happened because I ran contrib for an older version range and a newer version range. If we look in any particular file “directory” we find json files named by commit that had blame run.

$ ls .contrib/cache/libexec/cli/inspect.help/

045edd5c94822ae4f46c918399249f0dda38b6fc.json 83f6e979c533d09e0b5474fb40508238bb673a11.json

082ef81f751267b475bb918e7d1ca415567ebfe2.json 8f62c342009686990da5f0925d7f815edd110801.json

We can look in each json file and see the parsed blame:

{

"Vanessa Sochat": {

"libexec/cli/inspect.exec": {

"be6c7a85391e79e1273acc659410fbd17ced6d5f": {

"1495390269": 28

},

"cf8bbc36e1a97be04e779c5d0ab2f9a4a407cfdb": {

"1495597759": 5

}

}

},

"Gregory M. Kurtzer": {

"libexec/cli/inspect.exec": {

"3a9f9cf1e6369080c4676a8919e2cb09d8116e6e": {

"1496258562": 2

},

"2ad9d5862b7d1cea937044a23997bf66cd06695c": {

"1483468664": 2

},

...

What we see above are authors, file paths, and commits, timestamps, and then changed lines for each timestamp. To hammer down the point, the reason we have different commits for one blame (run for a commit) is because this represents the git blame for every line of the file at that timepoint. A change from a previous commit, even if it’s outside the commit, if it’s still present is going to show up! This is also why we keep the timestamps, because we can then filter this set down to include only commits that were within a desired range. But it also gives us the ability to see “all time credit” at any particular timestamp, which is pretty cool!

Once we parse a blame for a specific commit and file, we won’t need to parse

it again as it will be cached in (default) .contrib in the present working

directory. We can load that file and filter it for different contexts.

In the root of that same directory we also have a record of previously run ranges, which

are cached so we don’t have to load the individual files and filter them again. We also keep caches of other

information to help the multiprocessing workers, but we don’t need the details.

That’s it! This was a super fun little weekend project, and I suspect I’ll have more in the coming weeks related to it.