This is a crosspost from Jonathan Dursi, R&D computing at scale. See the original post here.

Pictured: The HPC community bravely holds off the incoming tide of new technologies and applications. Via the BBC.

This should be a golden age for High Performance Computing.

For decades, the work of developing algorithms and implementations for tackling simulation and data analysis problems at the largest possible scales was obscure if important work. Then, suddenly, in the mid-2000s, two problems — analyzing internet-scale data, and interpreting an incoming flood of genomics data — arrived on the scene with data volumes and performance requirements which seemed quite familiar to HPCers, but with a size of audience unlike anything that had come before.

Suddenly discussions of topics of scalability, accuracy, large-scale data storage, and distributed matrix arithmetic all became mainstream and urgent. The number of projects and workshops addressing these topics exploded, and new energy went into implementing solutions problems faced in these domains.

In that environment, one might expect that programmers with HPC experience – who have dealt routinely with terabytes and now petabytes of data, and have years or decades of experience with designing and optimizing distributed memory algorithms – would be in high demand.

They are not.

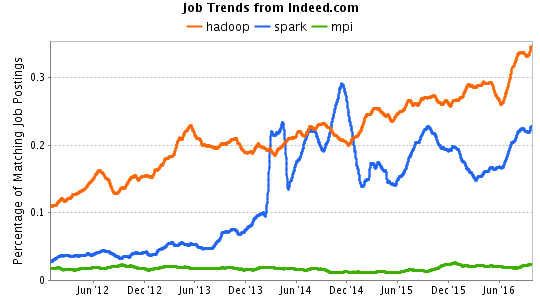

Indeed.com job trends data. Note that as many MPI jobs plotted above require certifications with “Master Patient Index” or “Meetings Professionals International” as are seeking someone who knows how to call MPI_Send.

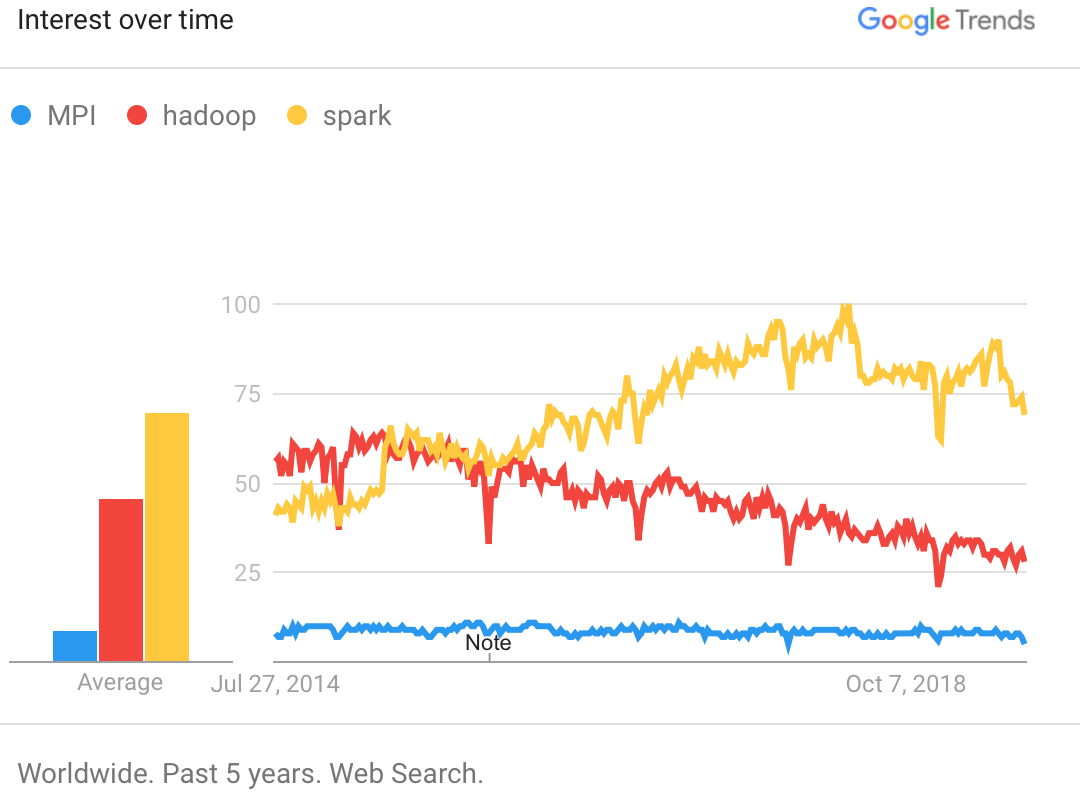

Google trends data for MPI, Hadoop, and Spark

Instead of relying on those with experience in existing HPC technology stacks or problems, people tackling these internet-scale machine learning problems and genomic data analysis tasks have been creating their own parallel computing stacks. New and rediscovered old ideas are flourishing in new ecosystems, and demand for scalable and accurate computation with these new tools is exploding — while the HPC community resolutely stays on the sidelines, occasionally cheering itself with hopeful assertions of relevance like SC14’s rather plaintive tagline, “HPC Matters”.

Because within the HPC community, the reaction to these new entrants is mostly not excitement at novel technologies and interesting new problems to solve, but scoffing at solutions which were Not Invented Here, and suggestions that those who use other platforms simply aren’t doing “real” high performance computing – and maybe don’t know what they’re doing at all. You can see this attitude even in otherwise well-researched and thought-out pieces, where the suggestion is that it is genomics researchers’ responsibility to alter what they are doing to better fit existing HPC toolsets. This thinking misses the rather important fact that it is HPC’s job to support researchers’ computing needs, rather than vice versa.

The idea that the people at Google doing large-scale machine learning problems (which involves huge sparse matrices) are oblivious to scale and numerical performance is just delusional. The suggestion that the genomics community is a helpless lot who just don’t know any better and need to be guided back to the one true path is no less so. The reality is simpler; HPC is wedded to a nearly 25-year old technology stack which doesn’t meet the needs of those communities, and if we were being honest with ourselves is meeting fewer and fewer of the needs of even our traditional user base.

If HPCers don’t start engaging with these other big-computing communities, both exporting our expertise to new platforms and starting to make use of new tools and technologies from within HPC and beyond, we risk serving an ever-narrowing sliver of big research computing. And eventually that last niche will vanish once other technologies can serve even their needs better.

Why MPI was so successful

MPI, long the lingua franca of HPC, has nothing to apologize for. It was inarguably one of the “killer apps” which supported the initial growth of cluster computing, helping shape what the computing world has become today. It supported a substantial majority of all supercomputing work scientists and engineers have relied upon for the past two-plus decades. Heroic work has gone into MPI implementations, and development of algorithms for such MPI features as collective operations. All of this work could be carried over to new platforms by a hypothetical HPC community that actively sought to engage with and help improve these new stacks.

MPI, the Message Passing Interface, began as a needed standardization above a dizzying array of high-performance network layers and often-proprietary libraries for communicating over these networks. It started with routines for explicitly sending and receiving messages, very useful collective operations (broadcast, reduce, etc.), and routines for describing layout of data in memory to more efficiently communicate that data. It eventually added sets of routines for implicit message passing (one-sided communications) and parallel I/O, but remained essentially at the transport layer, with sends and receives and gets and puts operating on strings of data of uniform types.

Why MPI is the wrong tool for today

But nothing lasts forever, and at the cutting edge of computing, a quarter-century is coming quite close to an eternity. Not only has MPI stayed largely the same in those 25 years, the idea that “everyone uses MPI” has made it nearly impossible for even made-in-HPC-land tools like Chapel or UPC to make any headway, much less quite different systems like Spark or Flink, meaning that HPC users are largely stuck with using an API which was a big improvement over anything else available 25 years ago, but now clearly shows its age. Today, MPI’s approach is hardly ever the best choice for anyone.

MPI is at the wrong level of abstraction for application writers

Programming at the transport layer, where every exchange of data has to be implemented with lovingly hand-crafted sends and receives or gets and puts, is an incredibly awkward fit for numerical application developers, who want to think in terms of distributed arrays, data frames, trees, or hash tables. Instead, with MPI, the researcher/developer needs to manually decompose these common data structures across processors, and every update of the data structure needs to be recast into a flurry of messages, synchronizations, and data exchange. And heaven forbid the developer thinks of a new, better way of decomposing the data in parallel once the program is already written. Because in that case, since a new decomposition changes which processors have to communicate and what data they have to send, every relevant line of MPI code needs to be completely rewritten. This does more than simply slow down development; the huge costs of restructuring parallel software puts up a huge barrier to improvement once a code is mostly working.

How much extra burden does working at this level of abstraction impose? Let’s take a look at a trivial example that’s pretty much a best-case scenario for MPI, an explicit solver for a 1D diffusion equation. Regular communications on a regular grid is just the sort of pattern that is most natural for MPI, and so you will find this example in just about every MPI tutorial out there.

At the end of this post are sample programs, written as similarly as possible, of solving the problem in MPI, Spark, and Chapel. I’d encourage you to scroll down and take a look. The lines of code count follows:

| Framework | Lines | Lines of Boilerplate |

|---|---|---|

| MPI+Python | 52 | 20+ |

| Spark+Python | 28 | 2 |

| Chapel | 20 | 1 |

Now, this isn’t an entirely fair comparison. It should be mentioned that in addition to the functionality of the MPI program, the Spark version is automatically fault-tolerant, and the Chapel version has features like automatically reading parameters from the command line. In addition, changing the data layout across processors in the Chapel version would only involve changing the variable declaration for the global arrays, and maybe writing some code to implement the decomposition in the unlikely event that your distributed array layout wasn’t already supported; similarly, in Spark, it would mean just changing the hash function used to assign partitions to items.

But even lacking those important additional functionalities, the MPI version is over twice as long as the others, with an amount of boilerplate that is itself the entire length of the Chapel program. The reason is quite simple. In Chapel, the basic abstraction is of a domain – a dense array, sparse array, graph, or what have you – that is distributed across processors. In Spark, it is a resiliant distributed dataset, a table distributed in one dimension. Either of those can map quite nicely onto various sorts of numerical applications. In MPI, the “abstraction“ is of a message. And thus the huge overhead in lines of code.

And this is by far the simplest case; introducing asynchronous communications, or multiple variables with differing layouts, or allowing processors to get out of sync, or requiring load balancing, causes levels of complexity explode. Even just moving to 2D, the amount of MPI boilerplate almost exactly doubles, whereas the only lines that change in the Chapel program is the array declaration and the line that actually executes the stencil computation.

On the one hand, this increase in complexity is perfectly reasonable; those are more challenging cases of networked computation. But on the other hand, of all available models, MPI is the only one where the researcher is required to reinvent from scratch the solutions to these problems inside the heart of their own application software. This requires them to focus on network programming instead of (say) differential-equation solving; and to completely re-architect the entire thing if their application needs change.

Now, none of this is necessarily a problem. Just because MPI is hugely and unnecessarily burdensome for individual scientists to use directly for complex applications, doesn’t mean that it’s bad, any more than (say) sockets or IB verbs programming is; it could be a useful network-hardware agnostic platform for higher-level tools to be built upon. Except…

MPI is at the wrong level of abstraction for tool builders

The original book on MPI, Using MPI, dedicated one of its ten chapters (“Parallel libraries”) to explicitly describing features intended to make it easier for tool builders to build libraries and tools based on MPI, and two others describing implementations and comparing to other models with relevance to tool-builders.

This was quite prescient; message-passing based frameworks would indeed soon become very important platforms for building complex parallel and distributed software in different communities. Erlang, released to the public just five years later, is a functional language with message-passing built in that has played a very large role in many communications and control environments. Rather more recently, Akka is a Scala-based message passing framework that, for instance, Spark is built on.

However, all these years later, while there are several specific numerical libraries built on MPI that MPI programs can use, there are no major general-purpose parallel programming frameworks that primarily use MPI as an underlying layer. Both GASNet (that UPC and Chapel implementations make use of) and Charm++ (a parallel computing framework often used for particle simulation methods, amongst other things) have MPI back ends, grudgingly, but they are specifically not recommended for use unless nothing else works; indeed, they have both chosen to re-architect the network-agnostic layer, at significant effort, themselves. (Of the two, GASNet is the more diplomatic about this, “…bypassing the MPI layer in order to provide the best possible performance”, whereas the Charm++ group finds MPI problematic enough that, if you must use MPI for “legacy” applications, they recommend using an MPI-like layer built ontop of Charm++, rather than building Charm++ on top of MPI). Similarly, the group implementing Global Arrays – an example come back to time and again in the MPI books – eventually implemented its own low level library, ARMCI.

Probably the closest to a truly MPI-based parallel scientific programming framework is Trilinos, which is a well-integrated set of libraries for meshing and numerics rather than a parallel programming model.

The reason for this disconnect is fairly straightforward. MPI was aimed at two sets of users – the researchers writing applications, and the toolmakers building higher-level tools. But compromises that were made to the semantics of MPI to make it easier to use and reason about for the scientists, such as the in-order guarantee and reliability of messages, made it very difficult to write efficient higher-level tools on top of.

A particularly strong case study of this dynamic is MPI-2’s one-sided communications, which were aimed squarely at tool developers (certainly a very small fraction of applications written directly in MPI ever used these features). This set of routines had extremely strict semantics, and as a result, they were soundly panned as being unfit for purpose, and more or less studiously ignored. MPI-3’s new one-sided communications routines, introduced 14 years later, largely fixes this; but by this point, with GASNet and ARMCI amongst others available and supporting multiple transports, and coming complete with attractive optional higher-level programming models, there’s little compelling reason to use MPI for this functionality.

MPI is more than you need for modest levels of parallelism

At HPC centres around the world, the large majority of HPC use is composed of jobs requiring 128 cores or fewer. At that point, most of the parallelism heavy lifting is best done by threading libraries. For the very modest level of inter-node IPC needed for these 2-4 node jobs, the bare-metal performance of MPI simply isn’t worth the bare-metal complexity. At that level of parallelism, for most applications almost any sensible framework, whether GASNet-based, or Charm++, or Spark, or down to Python multiprocessing or iPython cluster will give decent performance.

MPI is less than you need at extreme levels of parallelism

On the other hand, at the emerging extreme high end of supercomputing – the million-core level and up – the bare-metal aspect of MPI causes different sorts of problems.

The MTBF of modern motherboards is on the order of a few hundred thousand hours. If you’re running on a million cores (say 32,000 nodes or so) for a 24-hour day, failure of some node or another during the run becomes all but certain. At that point, fault-tolerance, and an ability to re-balance the computation on the altered set of resources, becomes essential.

Today, MPI’s error handling model is what it has always been; you can assign an errorhandler to be called when an error occurs in an MPI program, and when that happens you can… well, you can print a nice message before you crash, instead of crashing without the nice message.

This isn’t due to anyone’s lack of trying; the MPI Fault Tolerance Working Group has been doing yeomanlike work attempting to bring some level of real fault tolerance to MPI. But it’s a truly difficult problem, due in large part to the very strict semantics imposed by MPI. And after building up 25 years of legacy codes that use MPI, there is absolutely no chance that the pull of the future will exceed the drag of the past in the minds of the MPI Forum - none of those semantics will ever change, for backwards compability reasons.

Balancing and adapting to changing resources are similarly weak spots for the MPI approach; there’s no way that MPI can possibly be of any use in redistributing your computation for you, any more than you could expect TCP or Infiniband Verbs to automatically do that for you. If the highest-level abstraction a library supports is the message, there is no way that the library can know anything about what your data structures are or how they must be migrated.

Fault-tolerance and adaptation are of course genuinely challenging problems; but (for instance) Charm++ (and AMPI atop it) can do adaptation, and Spark can do fault tolerance. But that’s because they were architected differently.

Our users deserve the tools best for them

None of this is to say that MPI is bad. But after 25 years of successes, it’s become clear what the limitations are of having the communications layer written within the researchers’ application. And today those limitations are holding us and our users back, especially compared to what can be done with other alternatives that are already out there on the market.

And none of this is to say that we should uninstall MPI libraries from our clusters. For the near term, MPI will remain the best choice for codes that have to run on tens of thousands of cores and have relatively simple communications patterns.

But it’s always been true that different sorts of computational problems have required different sorts of parallel tools, and it’s time to start agressively exploring those that are already out there, and building on what we already have.

We have to start using these new tools when they make sense for our users; which is, demonstrably, quite often. It’s already gotten to the point where it’s irresponsible to teach grad students MPI without also exposing them to tools that other groups find useful.

The HPC community can, and should, be much more than just consumers of these external technologies. Our assertions of relevance don’t have to be purely aspirational. We have real expertise that can be brought to bear on these new problems and technologies. Excellent work has been done in MPI implementations on important problems like the network-agnostic layer, job launching, and collective algorithms. The people who wrote those network-agnostic layers are already looking into refactoring them into new projects that can be widely used in a variety of contexts, at lower levels of the stack.

But we need to give up the idea that there is a one-sized fits all approach to large-scale technical computing, and that it has always been and will always be MPI. Other groups are using different approaches for a reason; we can borrow from them to the benefit of our users, and contribute to those approaches to make them better.

We can build the future

There’s new ways of writing scalable code out there, and completely new classes of problems to tackle, many of which were totally inaccessible just years ago. Isn’t that why we got into this line of work? Why don’t more HPC centres have people contributing code to the Chapel project, and why isn’t everyone at least playing with Spark, which is trivial to get up and running on an HPC cluster? Why are we spending time scoffing at things, when we can instead be making big research computing better, faster, and bigger?

Are we the big research computing community, or the MPI community? Because one of those two has a bright and growing future.

Many thanks to my colleague Mike Nolta for many suggestions and improvements to this piece and the arguments it contains.

Appendix

(Update: see objections that came up after the publication of this post, on twitter and email, on this new post. And see what I like about MPI and why it suggests low-level applications programming isn’t the answer on the third post.)

Objections

But the HPC market is actually growing, so this is all clearly nonsense! Everything’s fine!

It’s completely true that, although much more slowly in relative or absolute terms than the Hadoop or Spark market, the HPC hardware market is still growing. But that’s not much of a reed to cling to.

Famously, minicomputer sales (things like System/36 or VAXen) were still growing rapidly a decade or so after personal computers started to be available, well into the mid-80s. They kept being sold, and faster and faster, because they were much better for the problems they were intended for — right up until the point that they weren’t.

Similarly, photo film sales were going up, if slower, until 2003(!). Let’s continue the disruptive innovation clichés as analogies for a moment — as we all now know, Kodak invented the digital camera. The film company’s problem wasn’t that it lacked the expertise that was needed in the new era; it simply flatly refused to use its expertise in these new ways. And as a result it is a shell of its former self today – a tiny, niche, player. Bringing the comparison closer to home is the experience of the once world-striding Blackberry, which ridiculed the iPhone as being, amongst other things, an inefficient user of network communications. (“It’s going to collapse the network!”)

Take a look at the market for developers. We’ve clearly passed the market peak for MPI programmers, and if HPC continues to be an MPI-only shop, our community will be shut out of the exciting things that are going on today, while many of our users begin being attracted by the benefits of these other approaches for their problems.

But MPI is much faster than the others because it’s bare metal!

If this is so important, why don’t HPC programmers save even more overhead by packing raw Infiniband frames themselves?

HPC programmers should know better than most that once you have some software that solves a complex problem well, getting it to go fast is comparatively straightforward, given enough developer hours.

It’s absolutely true that current MPI implementations, having had decades to work on it, have got screamingly fast MPI-1 functionality and, to a lesser extent, decent one-sided communications performance. But we live in an era where even JavaScript can have the same order-of-magnitude performance as C or Fortran - and JavaScript might as well have been explicitly designed to be un-en-fastable.

Chapel already can be as fast or faster than MPI in many common cases; indeed, higher level abstractions allow compilers and runtimes to make optimizations that can’t be performed one individual library calls.

And unless the basic abstractions used by Spark (RDDs) or Flink or the myriad of other options are inherently broken in some way to make fast implementations impossible — and there’s no evidence that they are — they too will get faster. There’s no reason why blazing-fast network communications should have be done at the application layer – in the code that is describing the actual scientific computation. The HPC community can choose to help with implementing that tuning, bringing their expertise and experience to bear. Or they can choose not to, in which case it will happen anyway, without them.

But MPI will adopt new feature X which will change everything!

Let me tell you a story.

MPI-1 and MPI-2 used 32-bit integers for all counts. This means that programs using MPI – the lingua franca of supercomputing, in an era when already outputing terabytes of data being routine – could not (for instance) write out more than 2e9 objects at once without taking some meaningless additional steps.

This was discussed at length in the process leading up to the 2012 release of MPI-3, the first .0 release in 14 years. After much discussion it was decided that changing things would be a “backwards compatability nightmare”, so the result was that the existing API… was left exactly as it is. But! There was a new larger data type, MPI_Count, which is used in a couple new routines (like MPI_Type_get_extent_X, in addition to the old MPI_Type_get_extent) which simplifies some of the pointless steps you have to take. Yay?

And that’s the story of how, in 2015, our self-imposed standard of supercomputing has a hardcoded in 32-bit limit throughout almost its entire API, limiting how many objects it can deal with at once without going through pointless but straightforward hoops. A 32-bit limit: 90’s retro-cool computing, like chiptune music and pixelated graphics with 8-bit color. This is unfortunate, but inevitable; after a tool has existed for 25 years, maintainers feel more responsibility towards the past than to the future. Which is perfectly reasonable, and maybe even the correct decision for that tool; but that’s when one need to start looking elsewhere for new projects.

But these other tools use programming languages I find to be icky.

Yes, well, perhaps the various alternatives involve languages that lack the austere beauty of Fortran and Matlab, but so it goes. One approach to this would be to help expand these tools reach into the HPC community by writing bindings and APIs for languages more familiar in this space.

But the Hadoop-y communities are incredibly naive about high performance interconnects, multicore/shared memory, complex scheduling,…

Yes! This is 100% true. And on the HPC community’s side, we’re quite innocent when it comes to fault tolerance at scale, building reusable tools, architecting APIs so that normal scientists can use them while hiding communications complexity beneath, and integrating nicely with systems industry cares about. There’s a window where we can help each other and contribute meaningfully to each groups success. But other communities can and will eventually figure out, say, multicore with or without our help.

Sample Code

Below are code samples referred to earlier in the piece.

MPI

Here is the 1D diffusion in MPI, Python:

#!/usr/bin/env python

import numpy

from mpi4py import MPI

def ranksProcs(): # boilerplate

comm = MPI.COMM_WORLD

rank = comm.Get_rank()

nprocs = comm.Get_size()

leftProc = rank-1 if rank > 0 else MPI.PROC_NULL

rightProc = rank+1 if rank < nprocs-1 else MPI.PROC_NULL

return (comm, rank, nprocs, leftProc, rightProc)

def localnitems(procnum, nprocs, nitems): # boilerplate

return (nitems + procnum)/nprocs

def myRange(procnum, nprocs, ncells): # boilerplate

start = 0

for p in xrange(procnum):

start = start + localnitems(p, nprocs, ncells)

locNcells = localnitems(procnum, nprocs, ncells)

end = start + locNcells - 1

return (start, locNcells, end)

def ICs(procnum, nprocs, ncells, leftX, rightX, ao, sigma):

start, locNcells, end = myRange(procnum, nprocs, ncells)

dx = (rightX-leftX)/(ncells-1)

startX = leftX + start*dx

x = numpy.arange(locNcells*1.0)*dx + startX

temperature = ao*numpy.exp(-(x*x)/(2.*sigma*sigma))

return temperature

def guardcellFill(data, comm, leftProc, rightProc, leftGC, rightGC): # boilerplate

rightData = numpy.array([-1.])

leftData = numpy.array([-1.])

comm.Sendrecv(data[1], leftProc, 1, rightData, rightProc, 1)

comm.Sendrecv(data[-2], rightProc, 2, leftData, leftProc, 2)

data[0] = leftGC if leftProc == MPI.PROC_NULL else leftData

data[-1] = rightGC if rightProc == MPI.PROC_NULL else rightData

return data

def timestep(olddata, coeff):

newdata = numpy.zeros_like(olddata)

newdata[1:-1] = olddata[1:-1] +

coeff*(olddata[0:-2] - 2.*olddata[1:-1] + olddata[2:])

return newdata

def simulation(ncells, nsteps, leftX=-10., rightX=+10., sigma=3., ao=1.,

coeff=.375):

comm, procnum, nprocs, leftProc, rightProc = ranksProcs()

T = ICs(procnum, nprocs, ncells, leftX, rightX, ao, sigma)

leftGC = T[0] # fixed BCs

rightGC = T[-1]

print "IC: ", procnum, T

for step in xrange(nsteps):

T = timestep(T, coeff)

guardcellFill(procnum, nprocs, T, comm, leftProc, rightProc,

leftGC, rightGC) # boilerplate

print "Final: ", procnum, T

if __name__ == "__main__":

simulation(100, 20)

Spark

1D diffusion in Spark, python (is fault-tolerant)

import numpy

from pyspark import SparkContext

def simulation(sc, ncells, nsteps, nprocs, leftX=-10., rightX=+10.,

sigma=3., ao=1., coeff=.375):

dx = (rightX-leftX)/(ncells-1)

def tempFromIdx(i):

x = leftX + dx*i + dx/2

return (i, ao*numpy.exp(-x*x/(2.*sigma*sigma)))

def interior(ix): # boilerplate

return (ix[0] > 0) and (ix[0] < ncells-1)

def stencil(item):

i,t = item

vals = [ (i,t) ]

cvals = [ (i, -2*coeff*t), (i-1, coeff*t), (i+1, coeff*t) ]

return vals + filter(interior, cvals)

temp = map(tempFromIdx,range(ncells))

data= sc.parallelize(temp).partitionBy(nprocs, rangePartitioner)

print "IC: "

print data.collect()

for step in xrange(nsteps):

print step

stencilParts = data.flatMap(stencil)

data = stencilParts.reduceByKey(lambda x,y:x+y)

print "Final: "

print data.collect()

if __name__ == "__main__":

sc = SparkContext(appName="SparkDiffusion")

simulation(sc, 100, 20, 4)

Chapel

1D diffusion in Chapel (can read parameters from command line)

use blockDist;

config var ncells = 100, nsteps = 20, leftX = -10.0, rightX = +10.0,

sigma = 3.0, ao = 1.0, coeff = .375;

proc main() {

const pDomain = {1..ncells} dmapped Block({1..ncells});

const interior = pDomain.expand(-1);

const dx = (rightX - leftX)/(ncells-1);

var x, temp, tempNew : [pDomain] real = 0.0;

forall i in pDomain do {

x[i] = leftX + (i-1)*dx;

temp[i] = ao*exp(-x[i]*x[i]/(2.0*sigma*sigma));

}

writeln("ICs: ", temp, "\n");

for step in [1..nsteps] do {

forall i in interior do

tempNew(i) = temp(i) + coeff*(temp(i-1) - 2.0*temp(i) + temp(i+1));

temp[interior] = tempNew[interior];

}

writeln("Final: ", temp);

}