This is a crosspost from Matthew Lincoln, PhD, The personal blog of Matthew D. Lincoln, PhD, data research specialist at the Getty Research Institute.. See the original post here.

Depending on how you count it, I’m the most junior dev on this panel, as I’ve only held the title of “software engineer” for one year now, since I joined Carnegie Mellon University last August. However, although the title was new, the work was not. I have been working in data modeling, analysis, and transformation since I began my dissertation nearly five years ago. After finishing my PhD in art history in 2016, I turned even closer to the programming track as I joined the Getty Research Institute as a data specialist, where I did both research as well as data engineering work on the Getty Provenance Index Databases.

But CMU has been the first time that my position has been explicitly named, and 100% devoted to, writing computer code to support digital humanities projects. I was very excited to take this step. My time at the Getty made me realize that architecting and implementing software systems was really where I was finding the most joy in my work. This talk will therefore be about three of the biggest shifts I’ve managed in this shift from implicit dev work to explicit dev work, and the and the survival strategies I’ve learned from them.

- Embrace the time zone change

- To be a good collaborator, you must be choosy

- Avoid the uncanny work plan valley

Embrace the time zone change

(no, I don’t just mean the shift from Los Angeles to Pittsburgh, although that certainly was a change.)

A month or so into my new gig, I tweeted out somewhat facetiously:

“I left the ‘research’ track and my time and expertise suddenly became way more valuable, way more respected, and way more protected! Also my skin cleared up and my hair is more luxuriant than ever."

— Matthew Lincoln (@matthewdlincoln) September 13, 2018

Although I was being a bit flippant, I still stand by the sentiment underlying that tweet. What I had observed was that my sense of both the magnitude, but also the character, of the way I and my organization valued my time had changed. As a PhD student, and to some extent as a Getty postdoc with the option to pursue a research agenda, it was easy to see my time as an abstract and unquantifiable entity. “Just add another meeting,” “Schedule this peer review,” “Travel for this conference,” “Get this article out,”… Although we all certainly talked about time management and being realistic about commitments in the abstract, rarely did I or my colleagues talk about our work as specifically budget-able.

I’d correctly anticipated that this would change when I moved to this new job. We seem to have collectively decided as a culture that computer programming can be valued in an instrumentalist manner, with projects budgeted by the hour, week, or mythical man-month. The effect that this had on my situation, where I was the sole developer dedicated to DH work, meant that my time was treated as a carefully guarded, valuable commodity. I found this to be an extremely welcome change!

To be clear, I don’t believe that there’s a fundamental reason that academic research time and software programming time should be perceived so differently. This difference is a socially-constructed one, but one that I was more than happy to embrace in this new role. I also want to be clear that this alternate mode of time valuing is not an automatic good. Speaking to other developers in the DH world, I was very aware of how a time-centric approach to doling out responsibilities could mean getting one’s week chopped up into impossibly small 5% increments. Switching gears (that is, working on one project in the morning, and then needing to shift attention to a different one in the afternoon,) is commonly viewed as an enormous waste of time when trying to write code.

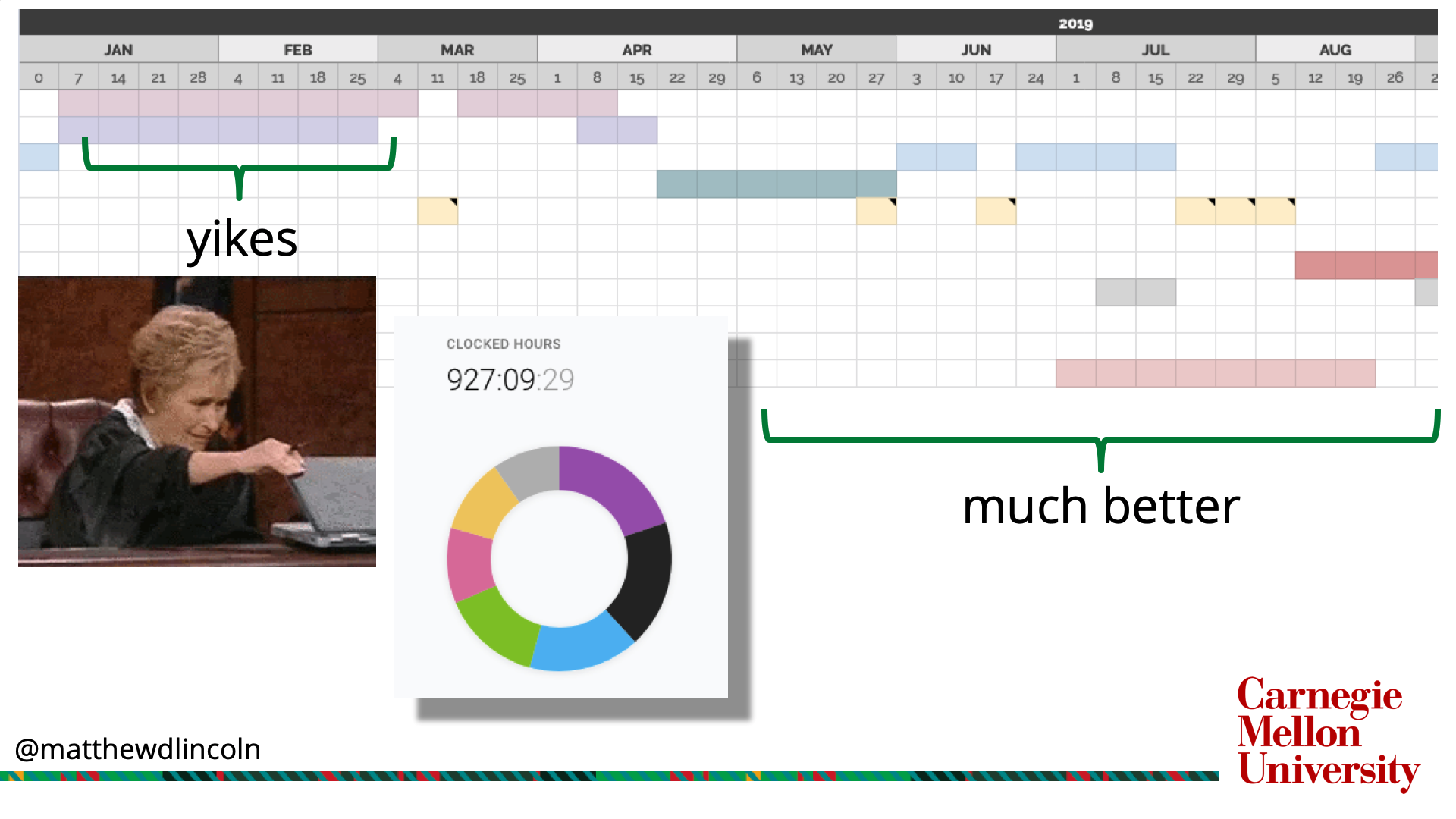

Tracking my week-by-week schedule in 2019 showed that my January and February were particularly unpleasant because I was trying to sprint on two different projects at the same time.

To that end, I began assiduously forecasting my work plans week-by-week on a year-long calendar in collaboration with my colleagues. I also started tracking my own minute-by-minute work during the day (I happen to be using Toggl, which has a very unobtrusive interface.) No one sees this more granular hour-by-hour time report except me. But I find it personally useful to see how much time I’ve actually spent on a project versus what I’d predicted it might take. Some days, it’s honestly been a useful reminder of when I should stop working because I’ve put in a solid 7.5 hours.

As much as I enjoyed this time-culture change, it presents challenges for working with faculty operating under very different time constructions. While I might have the privilege to schedule 3 weeks of dedicated work on a project, other members of the project team may have had their schedules chopped up like many academics do, between teaching, grading, writing, traveling, and committee work. I’ve needed to navigate how to be sensitive to this disjoint in how our time is structured, and to plan ahead to understand in which phases I would need their dedicated attention, and help set our mutual expectations accordingly. Figuring out how to achieve this is still an ongoing process for us.

To be a good collaborator, you must be choosy

In a one-person dev shop, you have to be choosy, even draconian, in declaring which technologies and frameworks you are going to learn and support. I came to CMU with above-average data chops, having programmed statistical analyses and data visualizations extensively in R for about 5 years.1 However I also knew that I had a lot of web development skills to catch up on to fill out the rest of my technical portfolio. While that landscape is truly vast, I’ve focused on Django for building websites that require complex data back-ends, while favoring Jekyll for anything that could be fit into that box. I’m also starting to pick up Vue (in conjunction with Django REST Framework) for web applications that need any kind of interactive interfaces beyond the most basic CRUD forms.

But even just pinning down those handful of frameworks in this first year gives me quite a lot of learning and programming to do in the coming year before I can call myself as fluent in them as I am in R. And so I don’t want to go adding on even more tools to my tool belt yet, lest I become a jack-of-all-trades, yet master of none. To that end, we pretty much don’t take on projects that can’t be handled with those technologies. We also make clear to our project teams that I’ll only be able to build them out prototypes of their projects, and that design work and implementation would need to be contracted out - an arrangement we’ve facilitated a few times so far to good effect. But being choosy like this is critical if I’m to be a good project collaborator who can give accurate time estimates.

Avoid the uncanny work plan valley

The uncanny valley of DH software work plans

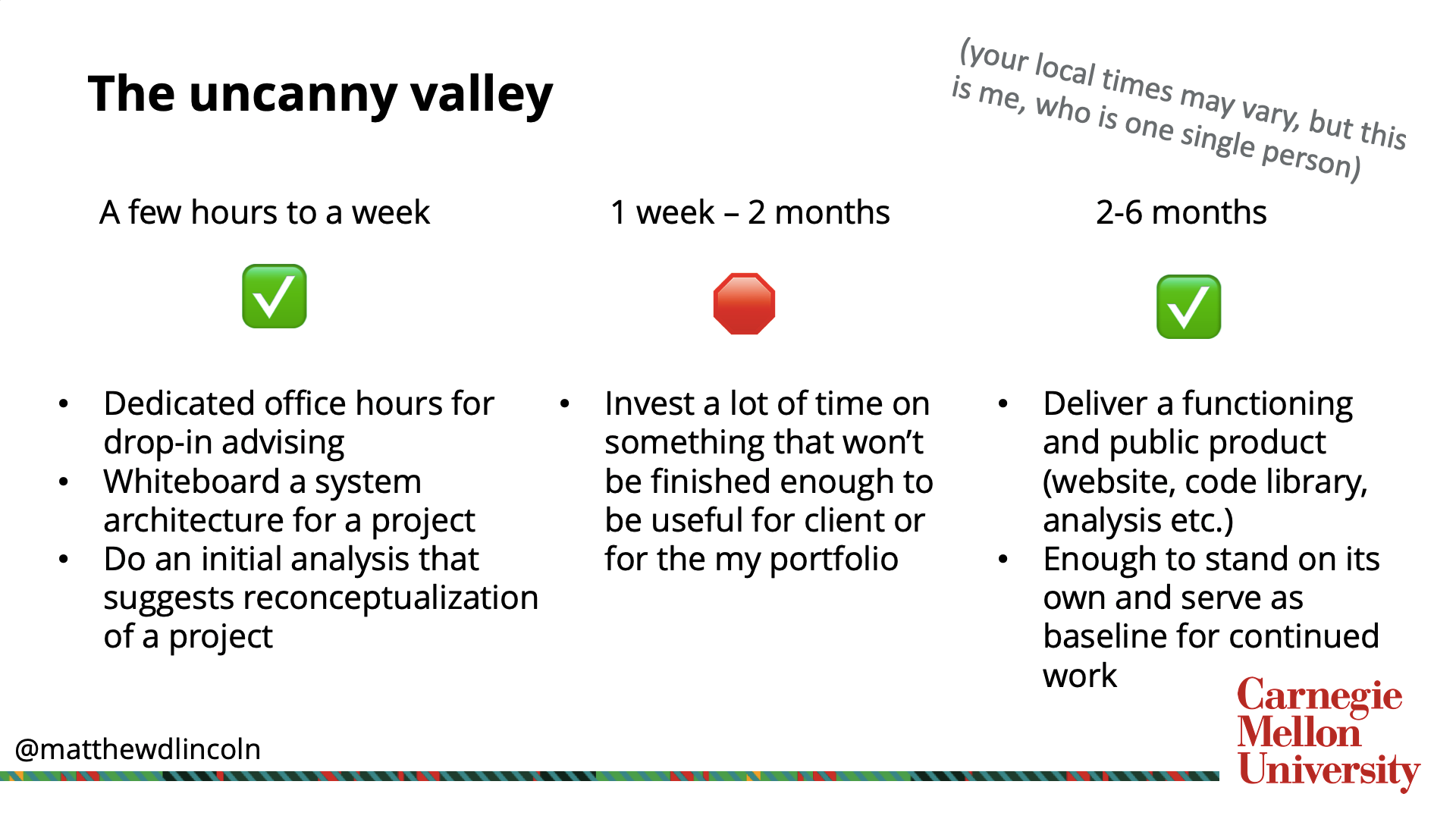

I’ve also been working on isolating what I call the “uncanny valley” of project scheduling.

On one side is is short engagements. Not every part of my work is integrated into a large and lengthy project. Our group at CMU libraries holds open office hours where we invite drop-ins from students, faculty, and staff who want short consultations on projects. And even though most of these short consultations don’t evolve into a finished product or analytical project, they’re generally useful for both parties involved. Our consultees get useful advice and starting points for their projects. We get to build community and get a sense of the work happening around campus with just a short, regular investment of time.

On the other side of the time scale is projects where I invest 2-6 months of work. At a large investment of time, these projects result in some kind of finished project such as a deployed website (for example, CMU’s Encyclopedia of the History of Science, or ETHOS) or a code library use in a research project (see konigsbergr, an R package built to find a path across all of the bridges in the city of Pittsburgh, but repurposeable to any city you’d like to put in to it.) These are obviously beneficial both to my clients, as well as to me, because I can point to them in our internal stakeholders who want to see what our resources are going to, and to my own professional portfolio.

In the 1 week to 2 month range, however, is the dreaded “uncanny valley” where I’d invest a lot of time, but not enough time to end up with an application or a data pipeline that is useful for our project team, and certainly not useful as a finished project to report to our associate dean, or to show off on my résumé. We have already used this uncanny valley measure as a factor in deciding when to join grants. When PIs see how including developer time consumes a surprisingly large amount of their budget, I’ve found they will propose incrementally shaving down the time commitment (and thus cost) of my work until it fits the funding cap for that grant. This is totally understandable on the part of the PI. When this cutting drops us into the uncanny valley, though, I’ll propose instead to substantially change my involvement so that we drop down into the “short engagement” green zone. I might suggest that I aid in a limited, but intensive architecture workshop with them to whiteboard out a project plan. But I would not commit to actually executing that plan on that particular grant, instead suggesting that they use that white-boarding, along with their other wok on that grant, to get the project to a state where it can afford fuller software development work.

By framing this conversation in a productive manner, demonstrating why I don’t want to consume a project’s budget without being able to deliver something that will be useful to the project team, we’ve been able to effectively stay out of the uncanny valley.

-

I’ve posted about one of my unexpectedly widespread R packages, clipr, and how it relates to DH development. 4.4 million downloads, as of the time I wrote this! ↩