This is a crosspost from Rebecca Sutton Koeser, RSE (Research Software Engineer) posts. See the original post here.

A Digital Humanities origin story.

In 2013, I had the privilege of attending Speaking in Code, a Digital Humanities developer summit on tacit knowledge and code as craft that was hosted by Scholars’ Lab. I was remembering that experience for a couple of reasons as I prepared for ACH2019 this summer. As I worked on my talk for the roundtable session on The State of Digital Humanities Software Development organized by Matthew Lincoln, I looked back at the proposal and remembered that it referenced Speaking in Code directly. I was also reminded of tacit knowledge in a different way, as I worked with my colleague and collaborator Gissoo Doroudian on a woven data physicalization for Data Beyond Vision. I discovered I had some of that tacit craftwork knowledge for working with yarn. It was easier for me to untangle the knots; I could follow the directions easily because I had a sense of how the weaving would work (even without using this particular type of loom); she did not know that you start with the yarn from inside the spool instead of outside (this keeps the yarn from rolling around as you pull it, and makes it less likely to tangle). Around the same time, we also had a conversation about how many different jargons there are in the room - developer, designer, and academic.

One of the outcomes from Speaking in Code was a series of “origin stories” from participants. We were all invited to contribute ours, but I never made the time to write one. As I prepared for the roundtable session, I decided it was finally time to write mine, and when it came up in the Q&A session I committed myself to doing so. This seems to be an important conversation not just for DH but also for the broader Research Software Engineer (RSE) community, because there are still no established career paths for RSEs.

Of the prompts that were provided, the one that always appealed to me was:

Did I start?

… because I don’t have a definitive answer to when I started.

How far back do I go?

Do I go back to the early years of college, when I decided to add a second major in Math/Computer Science1 (on very little basis of experience or any known skill) after previously deciding to major in English Literature (on the unscientific basis of the number of literature classes listed in the course catalog that I wanted to take)? I remember laughing with a friend my sophomore year: she had introduced me to email the previous year, and now I was majoring in Computer Science and learning to program.

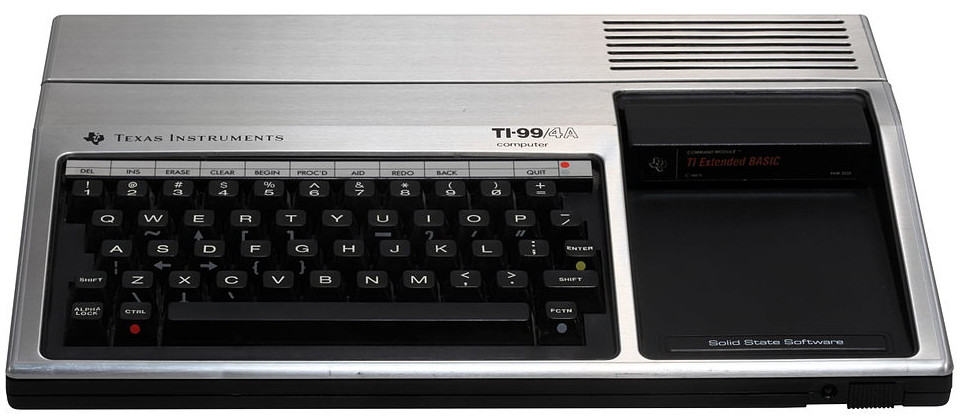

Do I go back to the TI99/4A that my dad set me in front of when I was four? He got me started playing a Towers of Hanoi game that he’d implemented in BASIC or Forth, and shortly after he stepped away I turned the computer off because I didn’t like the annoying beeps when I made an illegal move. I used to be embarrassed by this family story because I thought it exhibited my inability to master the simple logic of the Towers of Hanoi game, but I’ve since decided that it shows a certain mastery of computers.2

One possible beginning is the work I did on a website for the computer labs in college, where I worked first as a lab assistant and then a lab manager (back in the days when there were labs full of computers because not many students had their own). I remember learning HTML tags from a document called “Barebones HTML”.3

A more likely starting point is the work I did helping my Computer Science professor with his Christian Classics Ethereal Library project. I don’t remember the specifics, but I know we used SGML (Standard Generalized Markup Language) and I worked on a way to display Greek characters with images because Unicode wasn’t available yet.

Maybe I point back to the advice from Susan Opp, the Engineering Manager who interviewed me for the software company where I worked as a “Co-op Engineer” for two summers: she counseled me to pursue literature because it would be harder to come back to later. This might seem counter-intuitive, since the pace of technology changes so quickly, but she was right. Her words helped me make the decision to pursue graduate school in English Literature.

Another point on my journey was starting to work at the Beck Center my first year of grad school at Emory University. It was an electronic text center, including a wall of CD-ROMS with databases and specialty purchased software. I was “recruited” (encouraged to apply) by another grad student; he wanted more literature influence in the CD-ROM purchases, but I quickly ended up working on literary and historical texts encoded in TEI (Text Encoding Initiative) using markup language, first SGML and later XML (eXtensible Markup Language). I learned to program in PHP, more web development, and more in-depth XML technologies. I particularly remember working on The Civil War in America from the Illustrated London News (ILN) project, which we used as a testbed for trying new approaches, and where I implemented search and display of illustrations along with articles pulled out of the volumes of news. I also worked on a “Poetry Portal”, which provided search and browse functionality across poetry from multiple purchased and local collections in two different kinds of markup. I stumbled upon a set of poems that the encoding indicated should be right-aligned, and I happily added logic and styles to display the poems properly.

Undoubtedly, another step on my journey was choosing to take a position as a software engineer for Emory University Libraries after I completed my PhD. The people who hired me said that my PhD would be valuable for the work I would do, but it didn’t come into play as much as I thought. Certainly, it informed my work on the Electronic Thesis and Dissertation system, since I knew more about dissertations than the other developers on the team. We often speak of imposter syndrome; my version is that I didn’t consider myself “alt-ac” because the work I was doing wasn’t “academic” enough. There were some exceptions, such as the year when the Digital Scholarship Commons (DiSC, now Emory Center for Digital Scholarship) allowed staff to submit project ideas, and I was able to propose and then help create, in collaboration with Brian Croxall and others, the project that resulted in Belfast Group Poetry|Networks. I’ve had some amazing opportunities along the way: attending and presenting at DH conferences, being on the One Week | One Tool team that built Serendip-o-matic, and now working at the Center for Digital Humanities at Princeton.

I know now that I have been incredibly privileged: to have a mom who shared her love of reading with me but also helped me with math homework; to have a dad who shared his interest in computers and programming with me and not just my brother — although I didn’t really take advantage of it. I remember my dad dictating code for me to type into a Turtle drawing program he’d written in Forth (maybe when I was six or seven), but I don’t think I was all that impressed with the drawing generated by the code I’d typed. (I’m more impressed now at all the things my dad was doing with those early computers!) Even the lab assistant job in the computer labs was a valuable experience: I remember working on a computer in the lab after hours with a coiled phone cord stretched across the room so I could follow instructions to take apart a malfunctioning machine to determine if a motherboard was faulty and could be replaced. From all the stories I’ve heard and read, I was also privileged to go to a small Christian liberal arts college with an even smaller Computer Science program, where I was encouraged, and never insulted or harassed.

Photo of a university Computer lab. Our machines were beige with large CRT monitors, but I think we made the big upgrade to black machines while I was there. Public Domain

As I look at the other Speaking in Code origin stories, they are stories of individuality and encouragement.

Here is my encouragement to anyone trying to figure out how to start or if you belong: if you care, if you’re interested, then you’ve already started.

It’s ok to break things. I don’t mean this in the Silicon Valley sense of “move fast and break things”; break small things, your things. I’ve read that developers are atypical users: we’re more likely to tinker with the settings, not as worried about messing something up. I suspect this is because we have a better mental model of how computers and software work, and when things break, we’re likely to have some intuition about why (often the way things break is so informative). If you’re afraid to break things - figure out why, and do what you can to adjust and deepen your mental model of the world of the computer. It’s not as easy as it used to be to look at the source code of a webpage and figure out how something was built, but there are still plenty of ways to learn and investigate.

Keep asking questions. Another important step was early on at that Co-Op Engineer job. I was looking over a co-worker’s shoulder at his computer and saw him do something cool I hadn’t seen before (I can’t remember what, probably some kind of terminal shortcut or editor trick). I decided quickly that if I wanted to learn I had to ask questions, even if it made me look stupid; so I asked.4 And I continue to ask.

Learn more than one thing. Some people are good at algebra and bad at geometry, and for others it’s the reverse; some people prefer knitting to crochet, and others the opposite. You might find you understand one approach more easily than another, and learning more than one tool or skill give you a broader understanding of technology. My dad gave me a book on the programming language Perl, Perl by Example, as a Christmas present my sophomore year of college - and I, for some reason, read it. Learning Perl alongside the C++ I was taught in classes solidified programming concepts for me.

Work on things you care about. There are only so many times you can go through tutorials. I only really start to learn a new technology when I start making something of my own, even if it’s a small fraction of the thing I actually want to do. Your passion for your ultimate goals will carry you through the fits and starts of learning.

Thanks to my parents, who helped me with the details for several of these stories and gave me feedback on a draft.

Thanks also to my new colleague Grant Wythoff who read a draft and prompted me to clarify a few things.

Cross-posted on the Center for Digital Humanities at Princeton website.

-

At the time it was such a small department that there was no standalone Computer Science degree; the CS department split off from the Math department the year I graduated. ↩

-

I messaged my parents to get the details as I was writing this. Here’s how my dad recounted the story:

TI 99/4A, I think. Towers of Hanoi, probably written in Basic, but perhaps Forth. Sunday afternoon. Computer on table/desk in our bedroom. Program made an annoying “beep” sound if a bad play was made - i.e., a big ring on a small ring. I showed you how to play then got you started on a new game. I walked out of the bedroom and down the hall. When I got to the kitchen door, I heard the “beep”, and immediately turned around to see what happened. As I looked in the bedroom door you had already turned the computer off and left the chair in front of the table/desk. Apparently, you had quickly decided the computer was not going to get the best of you.

-

I can’t remember if we used CSS for that project; I’m fairly certain we didn’t use JavaScript. I looked up the dates CSS and JavaScript were invented and supported in browsers, because I was curious. CSS was proposed in 1994 and first supported by Internet Explorer 3 in 1996. JavaScript was created and available in Netscape Navigator 2.0 beta 3 in at the end of 1995. So, the technologies were around, but I don’t remember how prevalent they were; in any case, we didn’t need interactivity for the simple informational web pages I was helping with. ↩

-

Fun fact: I still prefer tcsh (totally cool shell!) for my terminal and I used Emacs for years (eventually I switched to Sublime Text with a plugin for Emacs key bindings. This was due in large part to the influence of the guys I worked with there, and the highly customized shell and editor config files they shared with me. ↩