This is a crosspost from Ian A. Cosden's Blog, Ian Cosden's Personal Blog on RSEs and Other Things. See the original post here.

What is an RSE?

This question has plagued me for months, maybe years. It’s been the subject of surprisingly opinionated discussions and intense debate within the community. I’ve come to the conclusion that, like it or not, definitions are important, perhaps critically important, because they create an identity. You can’t answer the questions “am I an RSE?” or “how do I become an RSE?” without defining the term RSE.

This post is my attempt, in a somewhat cohesive manner, to present my current thinking. I struggle with two somewhat conflicting definitions and have recently decided they don’t need to be mutually exclusive. I would like to openly welcome comments and feedback, because I don’t think this is close to being finalized. Community discussion and congenial debate is the way we are all going to sort this out. Reach out on twitter (@iancosden), the US-RSE Slack workspace (usrse.slack.com), or just email me (I’m sure you can find it).

The first RSE definition is fairly narrow and relates to my day job as the Manager of the Princeton Research Software Engineering Group. Since the group’s inception it’s been critical that I clearly define the mission of the group to the campus community. This means explaining what a RSE is to faculty, students, researchers, other research computing staff, and new RSEs themselves. I have to write job descriptions, arrange and assign projects, and supervise people explicitly in roles with the title “Research Software Engineer.” The definition of a Princeton RSE, therefore, has to be distinct and well-defined.

The second is a broader definition as it relates to the US-RSE Association. I’ve been actively involved in the organization since the beginning and I think it’s no secret that I am eager to see a professional association to support current and future RSEs. The goals of the organization are here and I’m 100% behind them. Many people have asked, and will continue to ask, “am I an RSE?” or “do I belong in the US-RSE?” In this context, the definition of what constitutes an RSE is essential as we strive to develop a unique group identity.

Recently I’ve come realize that that the Princeton RSE is just a subset or one of many possibilities that fits within the larger US-RSE definition. To illustrate this, I’ll start by explaining what we mean by a Research Software Engineer at Princeton (the narrower definition) and then step back to my interpretation of the broader umbrella definition we’ve settled on for the US-RSE Association.

What is a Princeton RSE?

Let’s start with the group’s mission, directly from our website:

Our mission is to help researchers create the most efficient, scalable, and sustainable

research codes possible in order to enable new scientific advances.

We do this by working directly with traditional academic research groups typically for long periods of time (months to years). The work can take many different forms including developing and implementing domain specific algorithms, creating reproducible computational workflows, porting and refactoring existing code, providing guidance on the design and construction of new software, optimization and performance tuning, and much more. This means we are essentially engaged in some or all of the research software development lifecycle.

Focused on the software

Research Software Engineers view the production of quality research software, typically for use by others, as the primary output of their work efforts. Note the difference as compared to a researcher whose primary work output is scientific discovery or insight (often measured in publications). A researcher - who will often spend a significant amount of time writing code, and can absolutely practice research software engineering - is typically motivated to write code as an intermediate step in an effort to produce a scholarly result. An RSE on the other hand, writes research software that is then used by, or used in collaboration with, someone else (i.e. a researcher) to produce that scholarly result. It’s something of a subtle difference, but the distinction has important implications. Incentives and motivations will necessarily be different.

Just to be rigorous, let me define what I mean by research software. I like the definition that the UK’s SSI used in a past survey on the subject. There they define research software as:

Software that is used to generate, process or analyse results that you intend to appear in a publication (either in a journal, conference paper, monograph, book or thesis). Research software can be anything from a few lines of code written by yourself, to a professionally developed software package.

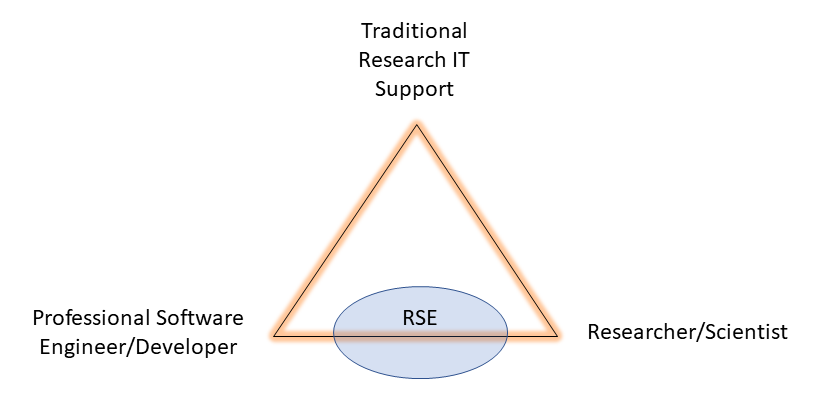

Many people like to define an RSE near the middle of the spectrum between a researcher and a software engineer/developer. It makes sense and I don’t have an issue with this, but I think it misses one additional distinction. And it’s centered around what an RSE is not. An RSE isn’t a helpdesk operator, facilitator, or user support specialist. These roles are critical, and arguably more important than an RSE, but they don’t view research software as the deliverable result of their work. Rather, these roles are rightly focused on making researchers more productive. The outputs of their work efforts are timely and effective removal of barriers in other people’s workflows. In some cases, this can absolutely involve RSE-type work, but on a whole, they are a separate entity - what I’ve been calling “Traditional Research IT Support.” The term “Facilitator” has been gaining some traction in the community recently and might even be a better term.

So we’ve determined that an RSE isn’t a researcher, and isn’t a facilitator, but RSEs aren’t really pure software engineers either. We’re definitely getting closer with the idea of a pure software engineer, but many times it’s still not right, or at least it’s not the entire story. The research workflow doesn’t often lend itself to a traditional software engineering consultancy where a client (i.e. the researcher) can provide a list of requirements and the software engineer can go off and build a solution. Instead, with an RSE, success typically requires more of a partnership, a back-and-forth collaboration between the RSE and the researchers, jointly working towards a solution. This frequently necessitates the RSE learning some of the underlying methodology, science, and/or statistics. This isn’t always the case, and we sometimes get involved in somewhat pure SE work, but there is a reason we adopted the term Research Software Engineer. It’s not just that it’s software engineering working on research software, but there is a component of research that almost invariably creeps into the workflow. An RSE that understands enough of the science to meet researchers halfway, stands to have a much greater impact.

You’ll notice in the schematic above (yes it’s barebones - I’m not a graphic designer!) that I’ve drawn the location of RSEs not as a point but as a bubble. How much research and how much software engineer depends on the person and the specific project, but typically lives somewhere in the middle.

I’m convinced this is why it’s so hard to pin down any definition of an RSE. The RSE, as I’m describing now, is not a researcher, not facilitator, not a system administrator, and not really even a software engineer, but something else. An RSE is a new role within the research software ecosystem.

Next up…what should a national definition of an RSE be?

What about the US-RSE?

The US-RSE has adopted (at for the time being) the following definition:

We like an inclusive definition of Research Software Engineers to encompass those who

regularly use expertise in programming to advance research. This includes researchers

who spend a significant amount of time programming, full-time software engineers writing

code to solve research problems, and those somewhere in-between. We aspire to apply the

skills and practices of software development to research to create more robust, manageable,

and sustainable research software.

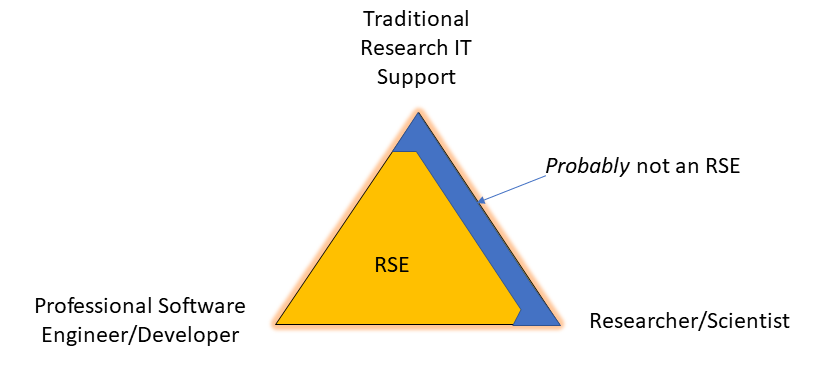

This is clearly different than what I just outlined for a Princeton RSE, as it directly includes researchers. At first (and maybe second or third) glance this appears to be irreconcilable with the notion that RSEs are not researchers.

But that’s not the case. With the goal to support and advocate for the RSE role in the research ecosystem we need to recognize that RSEs come in many different shapes and sizes. They might have a variety of responsibilities including tasks that no one would consider to be associated with an RSE. Does that mean they aren’t an RSE? Not at all. Let’s go back to my overly simplified triangle.

What is an RSE? As long as you stay away from the extreme non-software engineering, you just might be an RSE. Are you are using software engineering best practices and programming to advance research? You might be an RSE. Title is irrelevant. You could be a researcher, facilitator, programmer, post doc. If you are engaging in Research Software Engineering, and something about the above definition resonates, then you’re probably an RSE.

An RSE might support someone else’s research, or they might support their own. Regardless, if we are to believe that RSEs are making a critical contribution to the advancement of research then they should be getting credit for their software contributions. How to properly give credit for software is another topic of debate, and not one I want to get into here, but it underscores an important part of who would want to identify as an RSE. Do you want to be evaluated, rewarded, or acknowledged for the code you’ve developed and not just on the research output of that code? If so, you’re probably an RSE.

Final thoughts

I’m happy with having two different definitions for the same phrase. One is very specific, and one much broader. But are there only two? Almost certainly not, especially on the specific side. For example, I like the idea of a Super RSE extending into yet another dimension. The RSE Phenotype generator acknowledges the fact that RSEs might be so unique with multiple dimensions and facets, that individuals may need to define their own. In the end, I suspect most of the debate centered around “What is an RSE?” is probably related to this and is ultimately a variation of the blind men and an elephant parable.

The best path forward, in my opinion, is to lay out as many of specific definitions of RSEs, and then, as a community, we can define the elephant. It’s going to take time, be imperfect in the interim, and possibly even offend some people. These are growing pains. As long as we don’t lose the forest through the trees, we’ll sort it out.