This is a crosspost from Rebecca Sutton Koeser, RSE (Research Software Engineer) posts. See the original post here.

Text of a talk given as part of a roundtable on the state of Digital Humanities Software Development at ACH2019 with Matthew Lincoln, Zoe LeBlanc, and Jamie Folsom.

I’m going to talk a bit about software development best practices (as they are called), how I’m using them, and some of my questions and concerns about them.

First, a bit of background. I am the Lead Developer at the Center for Digital Humanities at Princeton where I lead our Development & Design Team. I think of it as a small team, but I know it’s more than many DH centers or even smaller libraries have. Our team is made up of one full-time developer, one half-time developer shared with another unit on campus, an 80% time User Experience (UX) designer, and myself.

I have formal training in both humanities and computer science: I have a PhD in English from Emory University, and in undergrad I double-majored in English Literature and Computer Science. I also have substantial practical experience in software development, most notably by working as a software developer for Emory University Libraries for ten years after I completed my PhD, where I learned software development best practices.

For my team at Princeton, I have put software development best practices in place in order to help us develop rigorous and maintainable software, in order to build things that work correctly and can be understood. However, most, if not all, of our software best practices come from industry where they are used to build commercial products. How well do they actually translate for research software? How can we use or adapt them in practical ways to get things done, and do them well, but still be critical and thoughtful in our process?

Agile

Many of the processes I’ve put in place come from Agile software development. If you’re not familiar, Agile is an umbrella term for several different lightweight methods including Rapid, Scrum, and Extreme Programming. Agile values include collaboration, communication (especially face to face), frequent delivery of working software, and embracing change. It’s worth taking a look at the Agile Manifesto; the values and principles are good, and there’s a lot that is appealing and easy to agree with. The manifesto is also available in over 60 languages, which is impressive.

I’m certainly not the first to point out that the 17 authors of the Agile Manifesto are all white men (for instance, see Agile is Fragile by Sarah Kaur in 2018). But not only that: they all worked in industry, and at least ten of them were consultants (many running their own firms) based on the brief author biographies on AgileManifesto.org.

Agile Manifesto authors. Image used in “Agile is Fragile” by Sarah Kaur (2018) with no credits; earliest use I could find is in a slide from a 2016 talk by Craig Smith, “40 Agile Methods in 40 Minutes”

The Agile Manifesto website has a list of the nearly 20,000 independent signatories who signed on as supporters of the manifesto from 2002 to 2016, when they stopped accepting signatures. Roughly half of those signatures include email addresses, but the emails listed on the site are overwhelmingly commercial (.com) addresses. Of course, this includes email providers like GMail and Yahoo, but it seems telling that there are more signatories from several individual countries than there are .edu emails.

Agile Manifesto signatory emails by top-level domain (top ten only) by year

Agile is associated with flexibility. In the commercial software world, that means adapting to the marketplace changing before you release your app. For us, that might mean a collaborator finds a new archival source that’s incredibly relevant but changes a project substantially.

I’m going to talk about three software practices we’re using and share some of my experiences with them.

User stories

A user story is a way of documenting software requirements from the end-user perspective, and it’s generally structured like this:

As a [who] I can do [what] so that [why].

Here are two examples of actual stories from development on Princeton Prosody Archive (PPA):

- As a content editor, I want to add edition notes so that I can document the copy of an item that’s in the archive.

- As a user, I want to see notes on a digitized work’s edition so that I’m aware of the specifics of the copy in PPA.

This structure documents the kind of user (as recognized by the system) that is allowed to use a feature and why they need it. It’s a written agreement between technical and non-technical project team members, that both can understand. It needs to be something that can be tested and verified, and it shouldn’t dictate the implementation - the developers decide that, informed by the why. I find this format useful, and we use stories like this to track development and document features in our project change logs (you can see them on our projects on GitHub). But this format is a challenge for our collaborators when they start working with us: they have to learn to read and write in this language.

Not only that; the user-centric approach that is common to Agile has been critiqued as being too consumer-oriented and taking away the subject’s agency. We probably all agree with this claim from Anne Burdick:

Software development methods suited to the creation of tools for shoppers or workers are a poor fit for the design of tools that embody the intentional fuzziness, nuanced positionalities, and reflexive activities of critical interpretation.

- “Meta!Meta!Meta! A Speculative Design Brief for the Digital Humanities” (Visible Language, 2015)

Burdick’s suggestions are interesting, but what she proposes is a design approach; I haven’t come across a practical solution for applying human-centered design to describing features for development. We’re fortunate to have a User Experience Designer on our team, who can do usability testing and user research, but I can’t help feeling there’s still some kind of gap here.

Story points

Story points are another tool from Agile. They are an arbitrary measure of complexity used to calculate and project team velocity. Estimation is typically done as a team, and it’s a valuable exercise to talk though upcoming features as a group with multiple perspectives.

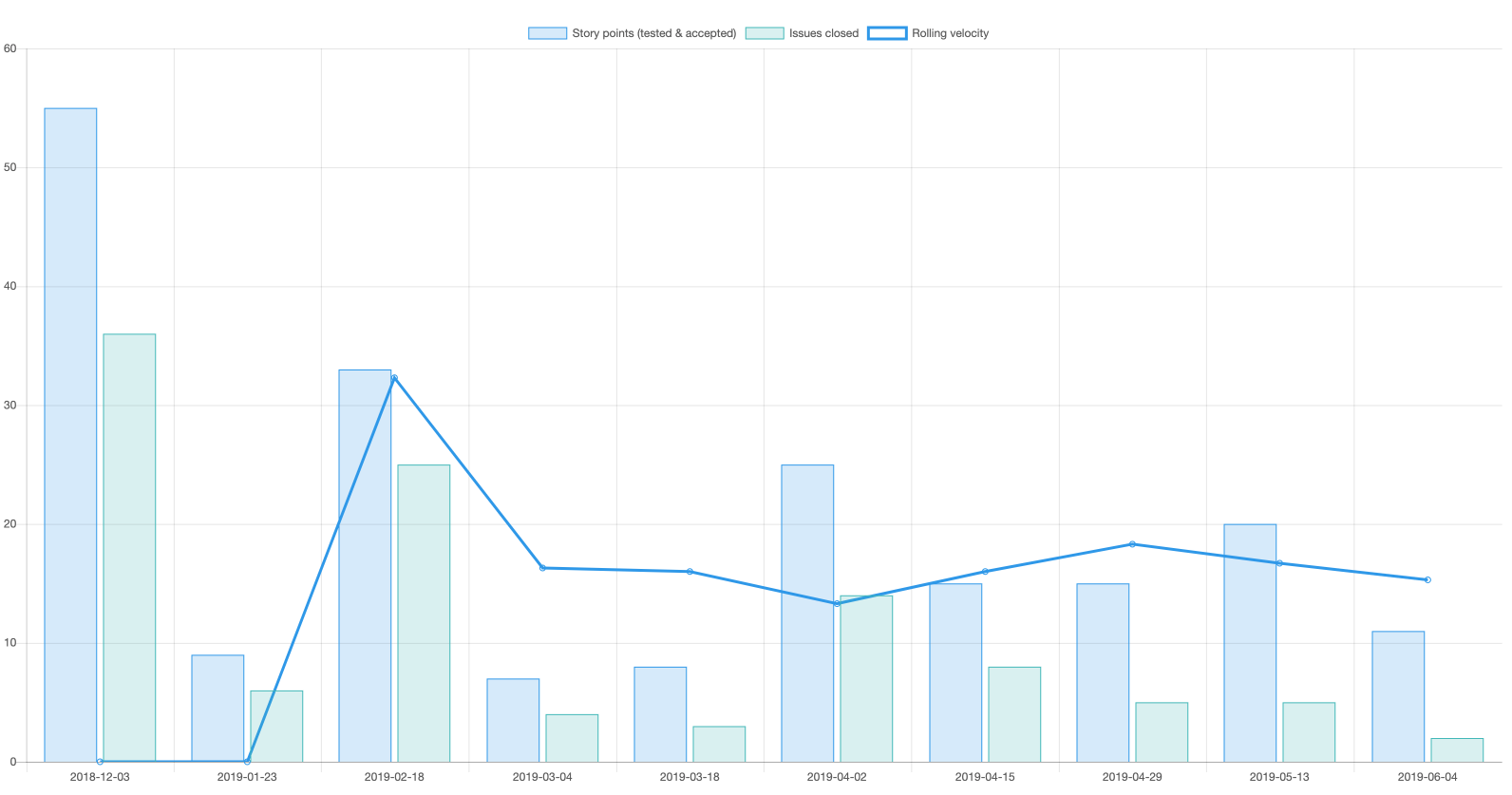

Here is an actual velocity chart I generated and shared with my team at an iteration retrospective meeting in June. The graph shows story points completed and issues closed for each two-week iteration, and a rolling velocity based on points for the last three iterations. We use the rolling velocity to help decide how much work to take on in the next two weeks.

CDH Princeton development velocity December 2018 - June 2019.

It’s typical to use the Fibonacci sequence for estimates: the bigger something is, the less we know, and it’s not worth quibbling over whether something is an 8 or a 9: it’s just big. For me, an estimate over 5 is a sign that the task is too big and should be broken down into smaller parts.

Planning poker cards. Photo by Nick Budak, CC BY 4.0

A few months ago I read about an alternate estimation scale that ranges from “everything is known” to “complete ignorance”:

- Just about everyone in the world has done this.

- Lots of people have done this, including someone on our team.

- Someone in our company has done this, or we have access to expertise.

- Someone in the world did this, but not in our organization (and probably at a competitor).

- Nobody in the world has ever done this before.

— Liz Keogh, Estimating Complexity

I find this approach interesting, because as developers writing research software, we’re living in that 4-5 zone. This means that development is going to be experimental and unpredictable.

To give you a recent example: on the Shakespeare and Company Project, we wanted to reconcile books from Sylvia Beach’s lending library to OCLC records. We hoped to automate the data work to reduce the manual labor required for cleaning up the nearly 8,000 book records. We had a large task (originally estimated as 5 points) that kept rolling over from one iteration to the next; we couldn’t complete it, because we’d framed it as investigating how to do the reconciliation. Eventually we broke it up into discrete steps, starting with a script to generate a report that project team members could review, so we could figure out how well the reconciliation was going to work and what to do next.

Minimum Viable Product (MVP)

A minimum viable product (MVP) is a product with just enough features to satisfy early customers, and to provide feedback for future product development.

— Definition from Wikipedia, Minimum Viable Product

The notion of an MVP (which comes from Lean software development) can be a useful scoping tool for DH projects: figure out how to start small, scale back from a grand vision into something that can be implemented in a shorter time frame and still be useful. But are we building a product? Who are our customers? How do we measure the value of new features when, unlike industry software firms, our standard is not how much money we make?

I’m becoming less certain that this actually works for scholarship.

- It’s hard to be minimal.

- How do we identify early adopters and then get them to actually use the project?

We have used MVPs or baseline feature lists in our CDH project charters, but I’m starting to question how useful it is, or if we’re doing it wrong. In some projects, it meant we got into specifics too soon and started quibbling over whether a particular search filter or field is essential. I’ve also learned that text-based lists of features, which make complete sense to me, don’t work for everyone; mockups are much more compelling and powerful. In one case, a design mockup actually lead our collaborators to think we’d implemented a feature that wasn’t even intended to be in the MVP.

How can you be minimal in your scope and still adapt to change? For instance, the Shakespeare and Company Project started out looking at lending library cards from the Sylvia Beach archive at Princeton, but then the Project Director discovered logbooks in the archive which include member subscription information for nearly the whole duration of the library. He knew the lending library cards were only extant for a subset of members, but without incorporating data from the logbooks he didn’t know what portion it represented. Including that new source was important, but was also a substantial expansion of scope.

We’ve tried an informal “soft launch” for some of our projects; for example, the Derrida’s Margins site was made public but we didn’t officially tell anyone about it. I’m still not sure how effective that was; people discovered it and discussed it on social media, and maybe we lost momentum by not taking advantage of that early interest. For Princeton Prosody Archive we shared an early version with PPA board members, which meant we had a roomful of experts looking at the site and talking about the project for a day. Some of them continued to use it for their scholarship, but we didn’t have channels for feedback after that meeting, and our project director didn’t want to share the preliminary site when one of the outcomes of that day was a decision to revisit the visual design.

A proper soft launch might be more of a closed beta with access restricted only to early adopters working with the project, but handling that access is something extra to implement and also raises concerns about being exclusionary.

Other kinds of scholarship have drafts and revisions, deadlines. Are there other, more scholarly ways of scoping projects and imposing limits that we could adapt for software?

etc….

There are plenty of other software development “best” practices I haven’t touched on that are worth discussing and thinking more about.

One the process side:

- Code review

- Time-boxed development (iterations or sprints)

- Retrospective meetings

- Acceptance testing

On the technical side:

- Unit tests

- Documentation

- Continuous integration

- Automated deploy

- Reusable code

Community & career paths

Software development best practices are difficult, if not impossible, to implement without a team or community. One possibility we might be able to leverage is the US Research Software Engineer Community (US-RSE). There are established RSE groups elsewhere that are much farther along, and I know the DH community is well-represented in the UK equivalent. The US organization is still getting started, which means DH developers have a chance to get involved, help shape the group, and ensure that it includes us.

See also Matthew Lincoln’s remarks from the same session: ‘What’s in a name?’ Transitioning from implicit to explicit software dev and the Twitter hashtag for the a wonderful audience live-tweeting the panel, including Q&A.