This is a crosspost from VanessaSaurus, dinosaurs, programming, and parsnips. See the original post here.

Nushell is a modern shell written in rust. I’m excited about the project because the landscape of shells hasn’t had much attention recently. You know, most of us are generally happy with bash, and it wouldn’t typically cross our minds that a shell might offer so much more.

It’s like we need a new shell! nushell?

I’ll encourage you to take a look at the The Nu Book and try out some of the Nushell containers for an easy way to try it out (hint, use the devel tag for the latest builds).

Too Long, Didn’t Read

While GoLang isn’t ideal for developing a binary that has lots of nested and varying inputs, in that a developer might want to develop a plugin that uses some Go library, it’s important to have a getting started example. nushell-plugin-len is that starting example, and I encourage contributions to help make it better.

Empower Others to Contribute

In talking about contribution of plugins, we are going to inadvertently talk about open source communities. Here’s the thing - developing software (or being a maintainer) is about so much more than putting code on GitHub. If a project makes it easy (or even fun!) to contribute, the project is more likely to be successful. On the other hand, if you choose to develop your software in a niche language, and find that only the core maintainers are the contributors, then you will have a much harder time. Why might this be?

- It's hard to contribute

- Communication isn't great between core developers and contributors

- It isn't very fun

or let’s flip these so we can describe good practices:

- It's easy to contribute

- Goals and next steps are openly discussed, maintainers are friendly to new contributors and questions.

- Working on the project, and with the prople, is fun!

You can probably think of the open source projects that you work on, and ask these three simple questions. A project doesn’t need to score highly on all points to be good to contribute to! For example, a project that is really fun for you might outweigh some negative factor that it takes a little prodding to figure out how to contribute. A project that is really easy to contribute to might offer a lot for you to learn, so you don’t care that much that it isn’t fun. You run into trouble when none of the positive practices are present.

An Elegant Plugin System

This is exactly what makes the nushell plugin framework so elegant. While the shell itself is implemented in rust (and rust is a steep learning curve, the plugin framework allows for any binary on the path to be discovered and registered as a plugin.

Let that sink in! Any binary that is named appropriately and can return an understood set of json responses can act as a plugin! This means that you don’t need to know rust to develop for nushell. You can create plugins in Python, ruby, GoLang (this example here), or pretty much whatever your little heart desires.

It’s also elegant because the discovery happens when the user starts the shell. I’ve seen a lot of plugin developers require the plugin to be compiled alongside the software, and while this is sometimes necessary, it makes it really hard to ask to use your special plugin on a shared resource, or even convince another person to re-compile their software. Given this discovery, I have questions about best practices for security when using nushell, but this is outside the scope of this post.

How does it work?

You can imagine it like a conversation between Nushell and the plugin. This is what happens after Nushell finds a binary on the path that starts with nu_plugin_*:

Discovery

- (Nushell) "Hello nu_plugin, can you tell me how to configure you?"

- (Plugin) "Sure nushell, my name is "len" and here is my usage and other metadata."

- (Nushell) "Your metadata looks great! I'll register you so the user can run 'len' to interact"

Interaction

We now add the user, who wants to calculate the length of some input, to the conversation.

- (Edward) "Oh! I know that 'len' is installed, let's ask for help len"

- (Nushell) "Oh yeah! I know about nu_plugin_len, here is his usage."

- (Edward) "Okay, I want to know the length of this string."

- (Nushell) "Hey nu_plugin_len, I know you're a filter, I'm going to start the filter."

- (Plugin) "Ready!"

- (Nushell) "Great! Here is the content to calculate the length for!"

- (Plugin) "The length is 9!"

- (Nushell) "Thanks! We're all done now, I'm going to end the filter."

- (Plugin) "Goodbye!"

Json Specification

While in my head I like to imagine binaries talking with one another, in reality this is actually working by way of the JsonRPC specification, so the interactions are json messages. I’ll show you some examples in this post.

Building the Plugin Locally

But first I’ll show you how to build the binary in Go, which we are going to use next to show the json responses. Clone the repository:

$ git clone https://github.com/vsoch/nushell-plugin-len

$ cd nushell-plugin-len

and if you have Go installed locally, you can use the Makefile to build the plugin

$ make

go build -o nu_plugin_len

And given that we have a sense of the inputs that the plugin expects, we can first test outside of nushell. We’ll start with discovery.

Discovery

Discovery happens by way of passing a json object with method == config.

Hello nu_plugin, can you tell me how to configure you?

$ ./nu_plugin_len

# This would be passed from Nushell when the plugin is found on the path

{"method":"config"}

The plugin responds with a jsonRPC response, with status “Ok”. I’ve parsed this out from a single line for your readability.

{

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"method": "response",

"params": {

"Ok": {

"name": "len",

"usage": "Return the length of a string",

"positional": [],

"rest_positional": null,

"named": {},

"is_filter": true

}

}

}

Start and End Filter

Starting and ending filters pass the method as begin_filter or end_filter.

(Nushell) Hey nu_plugin_len, I know you’re a filter, I’m going to start the filter.

$ ./nu_plugin_len

{"method":"begin_filter"}

# okay, I'm good with that.

{"jsonrpc":"2.0","method":"response","params":{"Ok":[]}}

(Nushell) Thanks! We’re all done now, I’m going to end the filter.

{"method":"end_filter"}

# sounds good. See you later!

{"jsonrpc":"2.0","method":"response","params":{"Ok":[]}}

The plugin exits after we finish.

Calculate Length

The actual request to do the filter passes an item, and the item is identified as a String primitive. I am going to split the stream input into two lines for your readability:

(Nushell) Great! Here is the content to calculate the length for!

$ ./nu_plugin_len

{"method":"filter", "params": {"item": {"Primitive": {"String": "oogabooga"}}, \

"tag":{"anchor":null,"span":{"end":10,"start":12}}}}

The length is 9!

And here is the response, again printed for easy reading:

{

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"method": "response",

"params": {

"Ok": [

{

"Ok": {

"Value": {

"item": {

"Primitive": {

"Int": 9

}

},

"tag": {

"anchor": null,

"span": {

"end": 2,

"start": 0

}

}

}

}

}

]

}

}

And actually, when you are testing locally (and perhaps don’t have a tag, since it comes from the input stream) I’ve designed the plugin so that it will generate one for you. Here is an example without the tag:

$ ./nu_plugin_len

{"method":"filter", "params": {"item": {"Primitive": {"String": "oogabooga"}}}}

{

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"method": "response",

"params": {

"Ok": [

{

"Ok": {

"Value": {

"item": {

"Primitive": {

"Int": 9

}

},

"tag": {

"anchor": null,

"span": {

"end": 0,

"start": 0

}

}

}

}

}

]

}

}

Building the Plugin with Nu

Once local testing had taken me as far as I could go, I knew that I wanted to test with nushell. Containers to the rescue! We are going to build a container first with a GoLang base to compile the plugin, and then we will copy the binary into quay.io/nushell/nu-base under /usr/local/bin for nushell to discover. Here is the relevant Dockerfile to do that:

FROM golang:1.13.1 as builder

# docker build -t vanessa/nushell-plugin-len .

WORKDIR /code

COPY . /code

RUN make

FROM quay.io/nushell/nu-base:devel

LABEL Maintainer vsochat@stanford.edu

COPY --from=builder /code/nu_plugin_len /usr/local/bin

Notice that we are using the devel tag of nu-base to ensure we get a recent build. And then build it!

$ docker build -t vanessa/nu-plugin-len .

Then shell inside - the default entrypoint is already the nushell.

$ docker run -it vanessa/nu-plugin-len

Once inside, you can use nu -l trace to confirm that nu discovered your plugin

on the path. Here we see that it did!

/code(add/circleci)> nu -l trace

...

TRACE nu::cli > Trying "/usr/local/bin/nu_plugin_len"

You can also (for newer versions of nu > 0.2.0) use help to see the command:

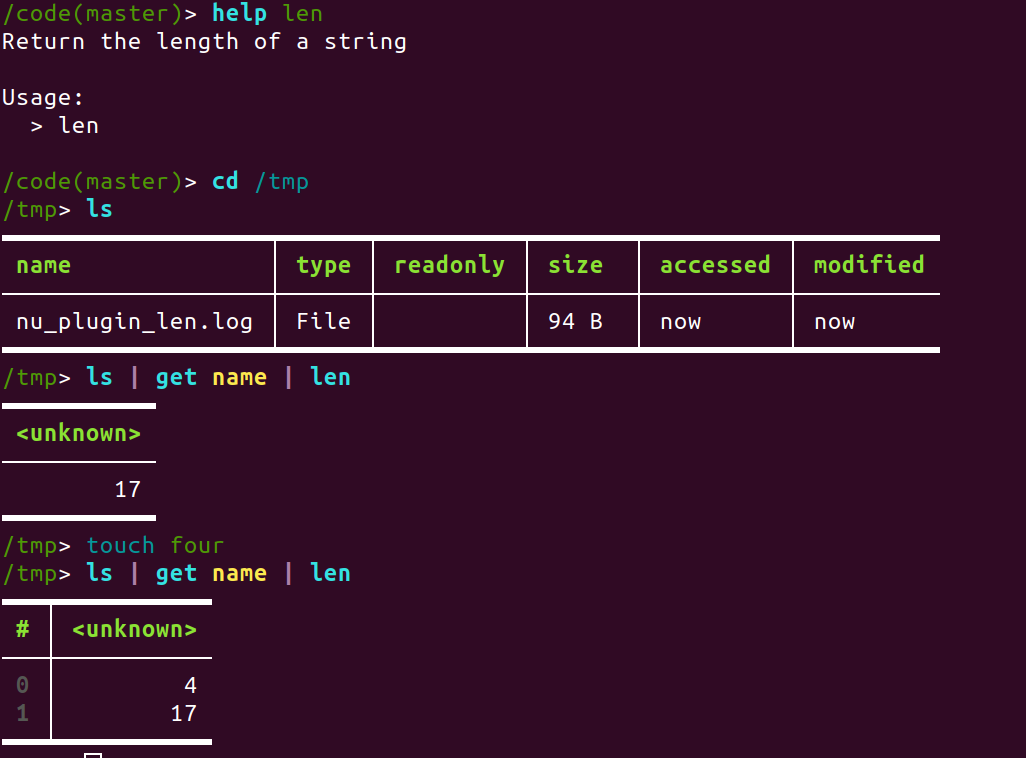

/code(master)> help len

Return the length of a string

Usage:

> len

/code(master)>

Now try calculating the length of something! Here we pass the string “four” into the length function, and nushell uses the plugin (with all the json message passing behind the scenes) to return to us that the answer is 4.

/code(master)> echo four | len

━━━━━━━━━━━

<unknown>

───────────

4

━━━━━━━━━━━

The plugin is a filter, which is why we can pipe into it.

Here is a slightly more fun example - here we are in a directory with one file named “myname” that is empty.

/tmp/test> ls

━━━━━━━━┯━━━━━━┯━━━━━━━━━━┯━━━━━━┯━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┯━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

name │ type │ readonly │ size │ accessed │ modified

────────┼──────┼──────────┼──────┼────────────────┼────────────────

myname │ File │ │ — │ 41 seconds ago │ 41 seconds ago

━━━━━━━━┷━━━━━━┷━━━━━━━━━━┷━━━━━━┷━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┷━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

Try listing, getting the name, and calculating the length.

/tmp/test> ls | get name | len

━━━━━━━━━━━

<unknown>

───────────

6

━━━━━━━━━━━

The above calculated that the length of “myname” is 6. Add another file to see the table get another row

touch four

/tmp/test> ls | get name | len

━━━┯━━━━━━━━━━━

# │ <unknown>

───┼───────────

0 │ 4

1 │ 6

━━━┷━━━━━━━━━━━

Docker Hub

If you don’t want to build but just want to play with the plugin, you can pull directly from Docker Hub

$ docker pull vanessa/nu-plugin-len

$ docker run -it vanessa/nu-plugin-len

Logging

A lot of figuring this out was trial and error, and then asking for feedback

or help on the nushell discord channel. The biggest help, by far, was

logging to a temporary file at /tmp/nu-plugin-len.log to fully see what

was being passed from nushell.

/tmp> cat /tmp/nu_plugin_len.log

nu_plugin_len 2019/10/16 15:01:02 Request for config map[jsonrpc:2.0 method:config params:[]]

nu_plugin_len 2019/10/16 15:01:16 Request for begin filter map[jsonrpc:2.0 method:begin_filter...

nu_plugin_len 2019/10/16 15:01:16 Request for filter map[jsonrpc:2.0 method:filter params:...

nu_plugin_len 2019/10/16 15:01:16 Request for end filter map[jsonrpc:2.0 method:end_filter params:[]]

I’d even go as far to say that nushell should have some “standard” way for organizing logs for plugins, since you can’t write logs to stdout.

Why?

The “So What” is that I want other developers and research software engineers to be empowered to contribute plugins, in whatever language they desire! Along with learning a bit about nushell and GoLang, this was my main goal for developing this. I hope that it is useful to you! Please contribute to nushell-plugin-len to make it better.