A. Philip Randolph, The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and the Invisible Labor of Research Software Engineers

Published: Jan 31, 2025 by Cordero Core

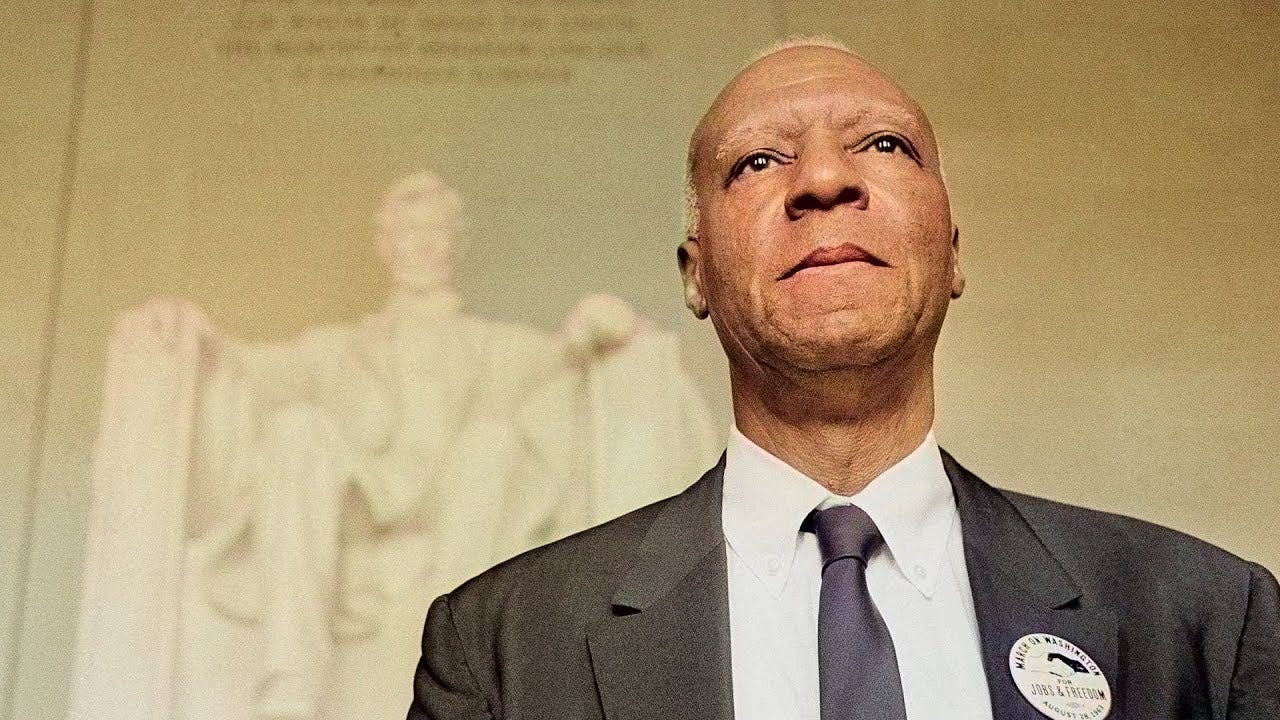

In 1925, A. Philip Randolph took on a challenge that many deemed impossible - organizing Black railroad porters into a union that would demand fair wages, humane working conditions, and respect. The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Maids became the first Black-led union to receive a charter from the American Federation of Labor, marking a pivotal moment in American labor history. Randolph understood something profound: labor, especially Black labor, was often unseen, undervalued, and dismissed. But through organization and collective action, the invisible could be made visible.

Nearly a century later, a different kind of labor remains invisible - the work of research software engineers (RSEs). They build the code that powers modern scientific discovery, yet many find themselves in an ambiguous space within academia and research institutions. Their contributions are fundamental, but their labor often goes unrecognized in publications, funding structures, and career pathways. This is not a coincidence. It is part of a larger historical pattern.

The Unseen Hands that Move the World

The sleeping car porters were integral to the expansion of American rail travel. They worked long hours under harsh conditions, often relying on tips rather than wages. They were expected to be invisible - to perform their work without complaint, to make passengers comfortable, and to disappear into the background. But their impact on American society was immense.

Research software engineers may not work on railroads, but their labor carries a similar paradox. They enable science to move forward - writing software that models climate change, processes astronomical data, and deciphers genetic codes. Yet, the very institutions that benefit from their labor often fail to formally recognize them. Many RSEs are classified as temporary workers, postdocs, or “other support staff,” despite their indispensable role in research.

Randolph understood that change would not come from individual effort alone - it required collective organization. The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters became a vehicle for economic mobility, civil rights, and structural change. Today, the US Research Software Engineer (US-RSE) community is doing similar work, advocating for the formal recognition of RSEs in academia and pushing for career paths that respect the reality of their contributions.

The Power of Naming and Recognition

One of Randolph’s greatest victories was securing the term “Brotherhood” in the name of the union. To be recognized as part of an organized workforce rather than just “servants” was revolutionary. Naming something - calling it what it is - is an act of power.

In research, the term Research Software Engineer did not exist in widespread use until the past decade. Before that, individuals who wrote software for research were often called “computational scientists,” “programmers,” or simply “support staff.” The adoption of RSE as a professional title mirrors the struggle of the porters: to be named is to be seen. To be seen is to demand recognition.

For many RSEs, their work is not just a technical function - it is a form of advocacy. They fight for open-source software, for better funding models, for institutional recognition. Just as the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters laid the groundwork for Black labor organizing, today’s RSEs are building the foundation for future generations of software engineers in research.

Labor is Political

Randolph understood that labor and civil rights were inseparable. He was not just organizing workers - he was challenging the racial and economic systems that shaped their exploitation. His work directly contributed to the broader Black freedom struggle, including the 1963 March on Washington, which he co-organized.

The fight for recognition in research may seem different, but it is no less political. It is about who gets to claim credit for discovery, who receives funding, and who has the stability to build long-term careers in science. Many RSEs, particularly those from underrepresented backgrounds, face additional barriers in these spaces. Their work is essential, yet they often find themselves excluded from the power structures that shape research priorities.

Randolph did not accept invisibility as fate. Neither should research software engineers.

The Path Forward

As we mark the 100th anniversary of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Maids, it is worth reflecting on what labor advocacy means today. RSEs, like the porters before them, are shaping the future through unseen, undervalued labor. Their work is critical, their contributions are real, and their fight for recognition is just beginning.

Randolph believed in the power of organizing, in the necessity of solidarity. The US-RSE community stands as a modern parallel - advocating for fair labor practices, recognition, and inclusion. The lesson from history is clear: no labor is truly invisible unless we allow it to be.

If research software engineers continue to build, organize, and demand recognition, they - like Randolph and the Brotherhood - will shape a future where their labor is seen, valued, and honored.

Stay tuned, share your thoughts, and be part of the conversation. How has invisible labor shaped your field? Let’s make history visible - together.

Join us on Slack in the

#dei-discussion channel.